Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter about technology and culture. This is a brief installment reflecting on the present moment. An audio version will follow separately, chiefly because I’m not a fan of how Substack audio posts now appear when shared online. A trifle to even mention in these days. Be well, friends.

Standing Sentinel

In a recent interview, Patricia Lockwood, who excels at voicing the experience of being extremely online, gave an apt and vivid metaphor for the all-too-familiar feeling that we must not take our eyes off the timeline.

In her 2021 novel, No One Is Talking About This, the protagonist lives her life online, in what she calls “the portal.” Lockwood was asked whether Twitter specifically, through which she staked her first claims to fame, functioned as “the portal” in her own life.

In the course of her response, Lockwood, refers back to her experience of the platform around 2016. “You felt that you had to be on there every day—” she writes, “like, 8 a.m., at your post—otherwise, you couldn’t control what was going to happen that day. If you didn’t know about it, then it would go on without you, beyond your control.” She then adds, “I think a lot of people, particularly in that time, felt that they were standing sentinel, which is, in many ways, a wasteful feeling.”

“Standing sentinel.” I can’t recall a more incisive formulation for the way many of us may experience being online at certain times. I especially appreciate the way Lockwood links this to some underlying, possibly inarticulate longing for control in what are, in fact, moments of extreme flux and disorder. This impulse may spring from the misguided belief that more information will automatically lead to greater clarity about what needs to be done, almost as if the accumulation of sufficient information will perforce reveal a plan of action eliminating the need for judgment.1 Judgment, after all, entails a measure of risk and responsibility, neither of which are especially welcome in our time.

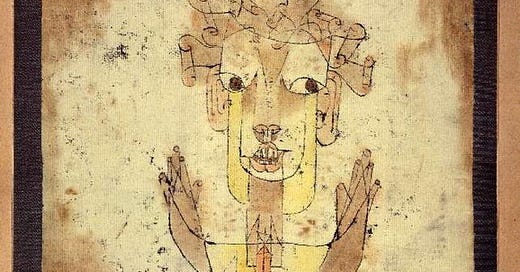

But I grant that this misguided desire for information is not the only reason one might feel compelled to stand sentinel at our digital outposts. The cascading spectacle which captures our attention has always, to my mind, recalled Benjamin’s description of the Angel of History, inspired by Klee’s “Angelus Novus.” “Where we perceive a chain of events,” Benjamin writes, “he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

So we stand gazing not at a sequence of events, but a wreckage hurled at our timeline by one algorithmically curated catastrophe after another. Like the Angel, we too may want to awaken the dead and make whole what has been smashed, but we have no such power. Which is perhaps why Lockwood calls the urge to stand sentinel “a wasteful feeling.”

Others may frame the urge to stand sentinel not as a coping mechanism for the anxieties of uncertainty or as a compulsion born out of catastrophe and helplessness, but as a moral duty, a duty to bear witness. I do not think we should lightly dismiss this framing. The ordinary impulse of the comfortable and secure is to turn away from the suffering of others, especially others who are not like them. It is the impulse to avert our eyes on passing the homeless woman whose look would trouble our conscience and disturb our peace.

I write this, of course, as another catastrophe unfolds in Ukraine, a catastrophe which may even bear within it the seeds of the unthinkable cataclysm. I’ve stood sentinel, I confess. Feeling at once the draw of the spectacle and the urge to bear witness, knowing, to some degree, the evident limits of both, and trying to embrace my own distinction between, on the one hand, having my attention captured and, on the other, attending to the world.2

But, I think I’ve felt something else, too, although I fear to name it. It is like a sculpture in ash that takes ineffable shape, so fragile that a breath, even spoken in acknowledgement, might undo it.

A Kind of Laughing Courage

Serendipity is one hell of a drug. I watch unfolding events while reading Tolkien and Arendt. The former has made me wonder whether in this moment we are seeing the “return of history,” as it has become fashionable to say, or rather the “return of myth.” The latter remains instructive as always about power, politics, and the human condition.

In the preface to Between Past and Future, Arendt explored the experience of those who, like the poet René Char, took an active part in the French Resistance during World War II. “The collapse of France,” Arendt wrote, “to them a totally unexpected, event, had emptied, from one day to the next, the political scene of their country, leaving it to the puppet-like antics of knaves or fools, and they who as a matter of course had never participated in the official business of the Third Republic were sucked into politics as though with the force of a vacuum.”

“Thus, without premonition and probably against their conscious inclinations,” she continues, “they had come to constitute willy-nilly a public realm where without the paraphernalia of officialdom and hidden from the eyes of friend and foe all relevant business in the affairs of the country was transacted in deed and word.”

“It did not last long,” Arendt acknowledges. “After a few short years they were liberated from what they originally had thought to be a ‘burden’ and thrown back into what they now knew to be the weightless irrelevance of their personal affairs, once more separated from ‘the world of reality’ by […] the ‘sad opaqueness’ of a private life centered about nothing but itself.”

Char himself had written that “if I survive, I know that I shall have to break with the aroma of these essential years, silently reject (not repress) my treasure.”

Allow me now to quote at length from Arendt:

“What was this treasure? As they themselves understood it, it seems to have consisted, as it were, of two interconnected parts: they had discovered that he who ‘joined the Resistance, found himself,’ that he ceased to be ‘in quest of [himself] without mastery, in naked unsatisfaction,’ that he no longer suspected himself

of ‘insincerity,’ of being ‘a carping, suspicious actor of life,’ that he could afford ‘to go naked.’ In this nakedness, stripped of all masks of those which society assigns to its members as well as those which the individual fabricates for himself in his psychological reactions against society they had been visited for the first time in their lives by an apparition of freedom, not, to be sure, because they acted against tyranny and things worse than tyranny this was true for every soldier in the Allied armies but because they had become ‘challengers,’ had taken the initiative upon themselves and therefore, without knowing or even noticing it, had begun to create that public space between themselves where freedom could appear. ‘At every meal that we eat together, freedom is invited to sit down. The chair remains vacant, but the place is set.’”

We are, I think, for reasons that are not altogether clear to me, standing sentinel because we are encountering not a treasure in quite the same sense that Arendt suggests here, but something like its distant echo—the rumor of a mode of life we’ve forgotten or been denied. But I’ll say nothing more of it.

Tolkien and Arendt have another curious commonality. They both made much of laughter. Throughout Tolkien’s most famous tale, the reader may be surprised to find some of the darkest, most perilous moments punctuated by a loud and sudden laughter. So it is, for example, when Eowyn, disguised to this point as an ordinary male solider named Dernhelm, reveals her true identity to the Lord of the Nazgul. “Hinder me? Thou fool. No living man may hinder me!” he says to her as she stands between him and her uncle the fallen king. After this we read the following:

“Then Merry heard of all sounds in that hour the strangest. It seemed that Dernhelm laughed, and the clear voice was like the ring of steel.

‘But no living man am I! You look upon a woman.’”

And so it is throughout the story: deepest darkness and despair unexpectedly pierced by laughter. For as he wrote in a letter to a critic, “It is precisely against the darkness of the world that comedy arises, and it is best when that is not hidden.”

For her part, Arendt believed that “laughter makes available confidence in our fellow man, confidence in the human power of resistance — against ideology and terror, against obscurantism, repression, dogmatism, and despotism.” She spoke of laughter as a form of “self-sovereignty” and elsewhere of a “kind of laughing courage.”

We have been plagued both by a pretentious and preening seriousness from certain quarters and equally pretentious frivolity from others, for which the best remedy may be laughter. “The laughter of incongruence, the laughter that erupts when facing absurdity,” as one scholar described the laughter Arendt commended.3 The laughter of witnessing the comedian lead his people through the darkest of times with sublime composure. And after all, does not the Angel seem to smile?

“Attending to the World”: The language of attention seems particularly loaded with economic and value-oriented metaphors, such as when we speak of paying attention or imagine our attention as a scarce resource we must either waste or horde. However, to my ears, the related language of attending to the world does not carry these same connotations. Attentionand attending are etymologically related to the Latin word attendere, which suggested among other things the idea of “stretching toward” something. I like this way of thinking about attention, not as a possession in limited supply, theoretically quantifiable, and ready to be exploited, but rather as a capacity to actively engage the world—to stretch ourselves toward it, to reach for it, to care for it, indeed, to tend it.

Marie Luise Knott in Unlearning with Hannah Arendt.

On standing sentinel, I think often of Auden's poem, (that I think we all read in high school), "Musee des Beaux Arts." I think about the first line, but I think the whole thing may be apropos. I'll past it below. I often check, more often than my Luddite sensibilites would have me admit, the New York Times website, and I find that I do so to bear witness. There's just not so much I can do about Vladimir Putin. Send him a nasty letter? But my daughter's college roomate is from the Ukraine, and his parents are in Kyiv, so, in that way, I am only a couple of degrees removed from that suffering. I was thinking about it yesterday. I had my bicycle's bottom bracket apart to repack the bearings, and there was pitting on the spindle that I was taking a long time to sand smooth, (not to mention make the spindle out of round, but everything can't be perfect can it?). "Here I am sanding, paying attention to these few defects in the metal, while an army invades a city that has done nothing to provoke it." I like to think there is some great, secret value in paying attention to the small things in ones own life, that somehow, that might create a cascading wave of good in the world, more than standing sentinel at the New York Times website, watching bombs explode in a short looping video. But as I sanded, I also thought of Auden's poem:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.