Assuming Responsibility for Time

The Convivial Society: Vol. 1, No. 7

“To hell with the future! It's a man-eating idol. Institutions have a future … but people have no future. People have only hope.”

— Ivan Illich, unpublished interview (1986)

The essay this week is a selection from a recent talk I gave on how we think about the future. I’ve trimmed it quite a bit, but it’s still longish. The gist of it is this: an older optimism about progress now gives way the urge to predict the future and both share a common trait, the refusal to accept responsibility for time. Following Arendt (and Auden), I suggest one mode of accepting responsibility for time and resisting the lure of both “Progress” and prediction is promise.

Enjoy, and thank you for reading. I hope you all are well.

When I was a kid growing up in the early 1980’s, I enjoyed perusing back issues of Popular Mechanics and Popular Science. I especially enjoyed flipping through issues devoted to imagining the future. You may remember them. They featured spectacular illustrations of massive space stations orbiting the earth and colonies on the moon and on Mars. They also foretold a future of automated labor, endless leisure, flawless medical care, and, yes, of course, more than a few flying cars.

Around the same time, Walt Disney World in Florida opened a second theme park then called Epcot Center. It, too, was themed largely around the wonders of science and technology. As you may already know, the name Epcot was an acronym standing for Experimental Prototype City of Tomorrow. It was the brain child of Walt Disney himself, who had intended for Epcot to be a working city, which would never cease to be a model for the future.

The actual park that opened back in 1982 was, of course, not a working city, but it was devoted to showcasing what the future had in store. I remember enjoying one ride in particular, which provided a moving journey through future scenes not unlike those featured in Popular Science and Popular Mechanics. The ride was called Horizons, and it was closed down in the mid-90s as Epcot began to shift its focus toward a more conventional theme park experience.

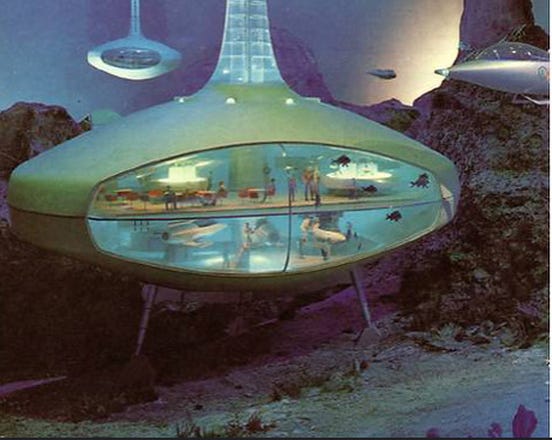

The panorama below greeted riders as they exited Horizons.

Looking back now on the world imagined in the pages of magazines and on theme park rides, it’s hard not to be both bemused and a little embarrassed.

It is not only the case that so much of the imagined future has never materialized or that these visionaries failed to anticipate some of the major developments that did arrive. It is also the case that some of what they triumphantly depicted now seems to us as wholly undesirable.

We would be colonizing the moon and Mars as well as the ocean depths and the deserts. For some reason it never occurred to me as a child that no one would actually want to live on the ocean floor. I’m always struck, too, when I remember that Horizons featured one particular scene that is now altogether jarring: you observed a kind of automated, laser-powered deforestation machine casually decimating the rain forests. Needless to say this hardly strikes a utopian note today. [Correction: I kept searching for this latter scene and eventually realized that it was not a part of Horizons but rather from The New Futurama, a ride that was a part of the 1964 New York World’s Fair.]

Interestingly, Epcot itself was a version of an older tradition that dates from the mid-19th century, the tradition of World’s Fairs and Expositions. These fairs were held throughout the world and were, not unlike what Epcot turned out to be, a mixture of pavilions dedicated to science and technology, often with a view to the future, alongside pavilions celebrating individual nations and their cultures.

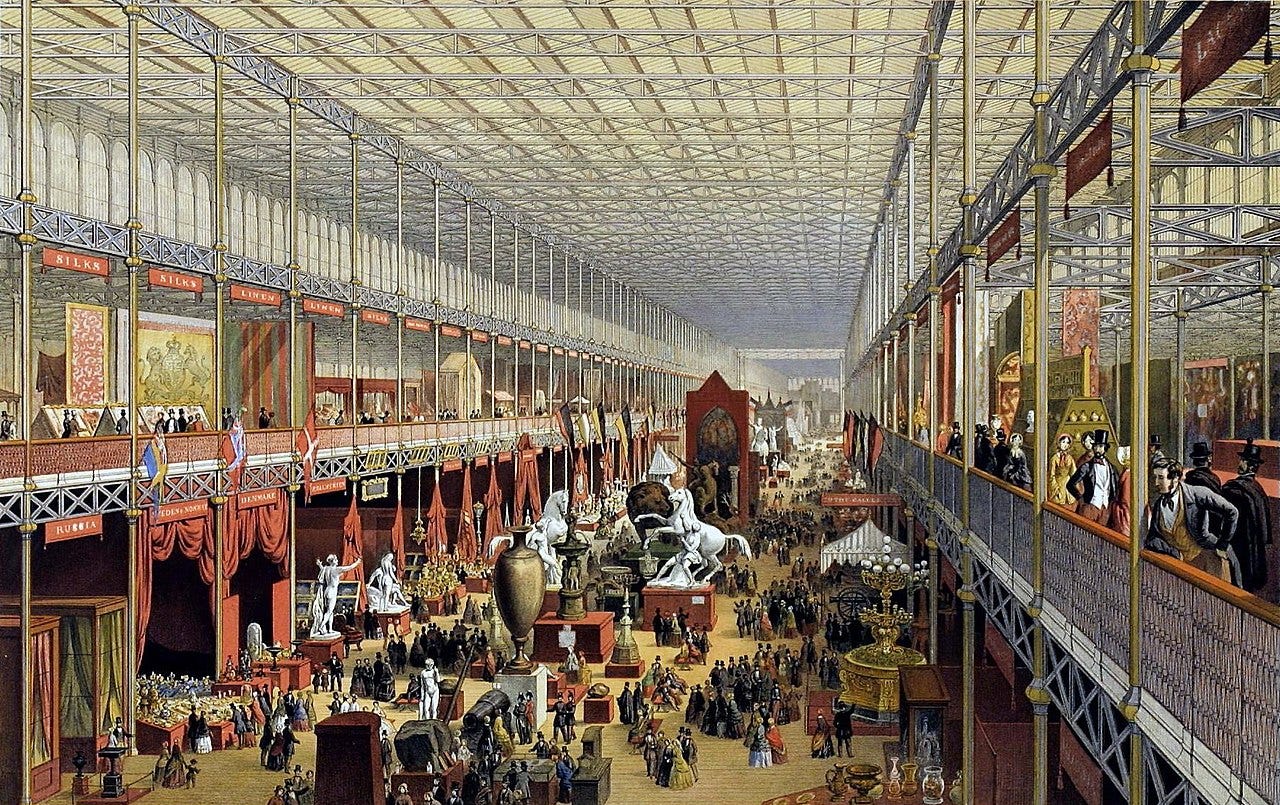

The history of these fairs is fascinating, and they tell us a lot about their cultural contexts (not all of it pleasant). The first fair of note was the Great Exhibition held in London in 1851. It was organized by Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, and its most famous feature was the massive Crystal Palace, which housed exhibitions of the latest industrial technologies. Below is an artists rendering of the interior of the Crystal Palace.

It was at the 1900 Paris Exposition that massive dynamos spinning with preternatural quiet while generating electric power so impressed themselves upon Henry Adams, later inspiring his famous reflections on the virgin and the dynamo as motive forces of cultural achievement.

The most famous fairs in America were arguably those held in New York in 1939 and 1964 and in Chicago in 1933. The two fairs of 1930’s placed a unique focus on the future. The most popular exhibits at the 1939 New York Fair were the World of Tomorrow and Futurama, a moving ride through scenic landscapes and cityscapes of the future that was a forerunner of Epcot’s Horizons.

These fairs were remarkable artifacts of modern confidence in the power of humanity to conquer nature and shape the future through science and technology thus ushering in a utopian society. The 1933 Chicago fair took as one of its slogan the impossibly dystopian line, “Science finds, industry applies, man conforms.”

It’s notable that these fairs were held during the decade we best remember for the Great Depression. The ’39 New York fair in particular was held not only as the world was in the grip of the Depression but also as the specter of a cataclysmic war was already looming over the world.

Nonetheless, or perhaps because of this, the fairs were extremely popular and were visited by millions of people in an age when air travel was not yet common.

We don’t do World’s Fairs anymore, at least not in this country. In fact, World’s Fairs are almost extinct. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, it was not unusual to have forty or more fairs or expositions per decade across the globe. Then the numbers begin to drop off around the mid-20th century. In the decade that just closed, there were only five world’s fairs and I’m willing to bet you didn’t hear about any of them. Only three are currently planned for this decade, and the first of these to be held in Dubai later this year will almost certainly be postponed.

Progress

The point of relating this brief history of world’s fairs is simple: the future isn’t what it used to be.

The fairs represented a thoroughly modern view of the future, a view which, as it turned out, was already losing its grip on the imagination.

By the modern view of the future I don’t mean the contemporary view, I mean rather the view of the future we associate with modernity, that is the set of assumptions, practices, and institutions that defined Western society from the seventeenth to the twentieth century, give or take a few decades on either end.

In his book exploring the origins of modernity, Michael Gillespie describes a key characteristic of the modern view of time in his discussion of the thought of the Elizabethan courtier and popularizer of the scientific method, Francis Bacon:

“Alluding to the discoveries of Columbus and Copernicus, Bacon … argued that modernity was superior to antiquity and laid out a methodology for attaining knowledge of the world that would carry humanity to even greater heights.”

This methodology is what we today tend to refer to as the scientific method based on observation, experimentation, and inductive reasoning. The key point, however, was Bacon’s insistence that the period in which he lived was superior to what had come before.

As Gillespie adds, Bacon “knew that this idea was deeply at odds with the prevailing prejudices of his age that looked to the ancients as unsurpassable models of perfection.”

Modernity, therefore, can be defined in part as a particular way of relating to time, one that breaks with the ancient prejudice for the past and casts its hopeful eyes toward the future. And here we begin to get a sense of how catastrophic the collapse of the myth of progress has been to the modern psyche. We might go so far as to say that the collapse of the myth of progress has been as traumatic for the modern world as the Copernican revolution was traumatic for the pre-modern world. Something that the core of society’s self-understanding was overturned in each case.

Needless to say, the modern ideal of Progress found its apotheosis in the United States, itself something new in the world, a nation that came to define itself by its lack of ancient traditions and institutions, a product of the New World bent on creating a new order for the ages.

A well-known 19th-century American painting neatly illustrates these developments: John Gast’s “American Progress” (1872).

Gast was commissioned by a publicist named George Crofutt, who instructed Gast to portray a “beautiful and charming female … floating westward through the air, bearing on her forehead the ‘Star of Empire.’”

The beautiful female was to carry a book in her right hand symbolizing the “common school—the emblem of education” while with her left, Crofutt’s instructions continued, she “unfolds and stretches the slender wires of the telegraph, that are to flash intelligence throughout the land.”

Crofutt also wanted Gast to depict certain elements “fleeing from ‘Progress.’” these included “the Indians, buffalo, wild horses, bears and other game.” The Indians were to “turn their despairing faces toward the setting sun, as they flee from the presence of wondrous vision. The ‘Star’ is too much for them.”

We know, of course, know how this tragic part of the story turned out.

The point I want to drive home here is this: this new way of imagining and relating to the future was not merely a disinterested assessment of the nature of things, it was a novel understanding of the history and it inspired optimism and dynamism. It was not only at the core of modernity’s self-understanding, it also accounted for modernity’s confident, well-nigh Promethean character. It sustained and empowered the modern project.

This matters still because we are all sons and daughter of the modern project. Even if we are critical of it, we cannot escape its influence. The culture we inhabit is a culture that was shaped by the modern view of time that we have been discussing, but it is also a culture that has been, by and large, disabused of these notions.

In the western world, the myth of progress and the attitude toward the future which it sustained received a fatal blow with the outbreak of the First World War. The Second World War, the Holocaust, and the threat of nuclear annihilation more or less rendered the idea of capital-P Progress implausible. Although it lingers in diminished form as an anxious and shallow fascination with the novel.

In our very recent history, the looming and unfolding consequences of climate change along with the turmoil of the Great Recession as well as the state of American political culture have all contributed this final disenchantment with whatever was left of the ideology of Progress.

If faith in progress played as critical a role in the modern imagination as I have been suggesting, then its eclipse has momentous consequences at both the personal and social level.

Prediction

Let’s turn our attention now to the recent fixation with predictive technologies. I’m doing so because these are of obvious interest if we are considering present attitudes toward the future. Their emergence and their allure may reveal something significant to us. We might take them as a symptom of a general disenchantment of the future.

Notable examples of such technologies include tools that purport to predict health outcomes including depression, genetically transmitted disease, and even impending death. These technologies, in other words, aim to predict our future well-being.

Others are designed to predict where crimes will occur, who will commit them, or the risk of recidivism among the imprisoned. They are deployed in the service of predictive policing as well as algorithmically derived sentencing guidelines and parole decisions.

Among the more dubious class of examples are those that aim to predict whether an applicant will be a good hire for a company, often by using voice and facial recognition software to assess whether an individual will be a good fit for the company.

It has been reported that Facebook is developing a tool to predict your future location. Other tools aim to predict whether couples are compatible. Some of the most common and by now mundane examples include recommendation algorithms that attempt to predict which products and services you might be most interested in. In the realm of search engine technology, Google long ago announced that it was no longer interested in merely serving you up answers to your search queries, it wanted to be able to serve you with information you didn’t yet know you wanted. The latter examples, especially, begin to disclose the relationship between predictive technologies and the desire to control or condition.

And this is to say nothing of the remarkably complex models deployed by meteorologists, climate scientists, financial institutions, insurance companies, and military strategists, too name just a few examples, in an effort to plot the range of possible outcomes for immensely complex processes. And, of course, we are all presently enthralled and divided by computer models which attempt to predict the future course of a pandemic.

The desire to predict the future, I’m going to suggest, reflects a fundamentally different attitude toward the future than that which was characteristic of high modernity.

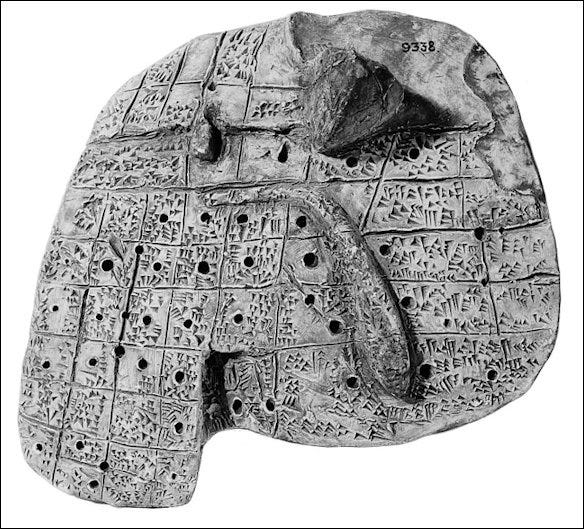

Of course, efforts to predict the future are hardly new. Some of the earliest extant written records from ancient Mesopotamia are, in fact, divination texts, which present meticulous protocols for priests who were attempting to read signs of the future in all manner of natural phenomena.

This next image, by the way, is an ancient Mesopotamian clay model of a sheep’s liver used as a guide to haruspicy, divining the future by examining animal entrails.

Our orientation to the past, of course, is characterized chiefly by its irrevocability, and our orientation to the future chiefly by its openness. So, naturally, we focus our efforts on what we can change or else prepare for.

Interestingly, ancient divination was not always a matter of determining what will necessarily happen within an immutable causal chain of events. The future that was being divined was often conditional, resting as it did on the judgment of the gods. As with the prophetic witness in ancient Israel, the point was not to report the future but to change it. An early reminder that the work of prediction is never really the work of reporting as much as it is producing the future. To utter a prediction is, paradoxically, to alter the future.

But there is one important observation to register here and that is the contrast between imagining the future, as the visionaries and futurists of the modern era were wont to do, and predicting the future, to which so many resources are now increasingly devoted. The former bespeaks a measure of confidence, the latter betrays an underlying insecurity.

Along these lines, it is is also worth noting that ancient divination was born out of a fundamental anxiety about the capricious and inscrutable character of the future, which was determined by the fickle will of the gods or the unknowable determinations of Fate. Our more recent efforts to forecast not just the weather, but the patterns of the social world betray a similar measure of anxiety.

Predictive technologies aim to mitigate or eliminate uncertainty and to foreclose the terrifying openness of the future. But when we turn to predictive technologies, what are we outsourcing? Human judgment? Responsibility? Or what do they displace? If they aim to relieve anxiety, might they also negate hope or undermine the conditions for meaningful action?

I hope it is obvious that I'm not laying out a case against all efforts at prognostication. Clearly it is imperative that we think about the future. It is the case, however, that we can conceive of rightly and badly ordered relationships to the future. We should be clear about what exactly we are seeking when we seek to predict the future? Or, what motives drive our efforts?

Promise

Let’s step back for a moment and consider these first two points in relation to one another. On the one hand we have the eclipse of the myth of progress. On the other you have a growing demand for predictive technologies.

Modernity traded the relative stability that characterized traditional society for the dynamism of creative destruction underwritten by the confidence that the creative would outweigh the destructive indefinitely.

As a result of the cultural and ideological trajectory along which we have traveled, we now seem to have neither the satisfactions of stability and continuity nor the consolation of believing that things will continue to get better for you and for your children. Moreover, older models of hope were displaced by an optimism about the potentials of Progress. It would seem that the older habits of hope are now less accessible just as the shallowness of mere optimism becomes increasingly evident.

We might also observe, however, that the earlier enthusiasm and energy born out of a belief that things will inevitably get better as well as the present attempts to predict and control the future born of deep insecurity share an intriguing similarity.

In a poem titled “Their Lonely Betters,” W. H. Auden’s narrator observes the creatures in his garden and reflects on their inarticulate natures":

“Not one of them was capable of lying,

There was not one which knew that it was dying

Or could have with a rhythm or a rhyme

Assumed responsibility for time.”

It is that last line to which I want to draw our attention. What both the old confidence and the new anxiety-induced drive to predict the future tend to have in common is a refusal to assume responsibility for time.

If the future is characterized by inexorable progress, I cannot be responsible for it.

If the future is subject to prediction, crassly understood, I cannot be responsible for it.

In both cases, the future is inevitable, whether because of the dispensations of technologically empowered ideology or ideologically laced technology, and if the future is inevitable there is no way to assume responsibility for time.

I've learned a great deal from Hannah Arendt. I've particularly appreciated her emphasis not on mortality but on natality—not death but birth that—as well as her appreciation of the giftedness of the existence. There is a threshold, it seems to me, that predictive technologies, quite apart from their accuracy or effectiveness, threatens to push us through with regards to our fundamental experience of what is to come, of what is new and unexpected, full of both promise and peril. Our desire is, of course, to eliminate the peril, but as with all such efforts, we may find ourselves unwittingly eroding the promise as well.

Arendt, who was not a religious believer, nonetheless evoked religious language in order to articulate the value of natality, of what is new erupting into existence with each birth.

"The miracle that saves the world,” she wrote, “from its normal, ‘natural’ ruin is ultimately the fact of natality.” “It is, in other words,” she continued, “the birth of new men and the new beginning, the action they are capable of by virtue of being born. Only the full experience of this capacity can bestow upon human affairs faith and hope, those two essential characteristics of human existence which Greek antiquity ignored altogether ….”

“It is this faith in and hope for the world,” Arendt continued, “that found perhaps its most glorious and most succinct expression in the few words with which the Gospels announced their ‘glad tidings’: ‘A child has been born unto us.’”

Hope, Arendt argued, was grounded in the fundamentally unpredictable nature of human natality. Each new birth carried with it the promise of the unexpected and generative.

The effort to predict the future, at least with regards to human affairs, entails the refusal of such uncertainty, which also turns out to be a refusal of human freedom and responsibility.

In a similar spirit, Wendell Berry in one of his Sabbath poems reminded us that “We live the given life and not the planned.” The perfectly planned life, that is to say the life that unfolds exactly as we predict, is no longer a given life; it loses its gifted character and becomes, strictly speaking, a fabricated life.

Auden closed “Their Lonely Betters, with the following lines:

“Let them leave language to their lonely betters

Who count some days and long for certain letters;

We, too, make noises when we laugh or weep:

Words are for those with promises to keep.”

The implication of the last line is that the making of promises is at least one way in which we might assume responsibility for time.

For her part, Arendt understood that the capacity to promise and to forgive arise, as she wrote,

“directly out of the will to live together with others in the mode of acting and speaking. If without action and speech, without the articulation of natality, we would be doomed to swing forever in the ever-recurring cycle of becoming, then without the faculty to undo what we have done and to control at least partially the processes they have let loose, we would be the victims of an automatic necessity bearing all the marks of the inexorable laws which … were supposed to constitute the outstanding characteristic of the natural process.”

In short, she understood that if we were to accept in the present the challenge of acting and speaking what is new into the world, then we must also find a way to relate constructively to the past and to the future, thus her insistence on the necessity of forgiveness and promise.

“The possible redemption from the predicament of irreversibility—of being unable to undo what one has done—” Arendt wrote, “is the faculty of forgiving.”

“The remedy for unpredictability,” she continued, “for the chaotic uncertainty of the future, is contained in the faculty to make and keep promises.”

Notably, she does not indicate that the remedy for the unpredictability of the future is to achieve the capacity to predict it. Unlike prediction, a promise is a way of assuming responsibility. It does so chiefly by drawing the agent directly into the fray. The one who predicts invariably speaks in the language of abstraction—such and such will happen—and evades responsibility for their role in the unfolding of time. The one who promises cannot help but do so by brining herself to the center of the action. It is always an “I” that promises, and in this way assumes responsibility for what is to come.

As the contemporary German philosopher Vanessa Lemm has put it, “For Arendt, the faculty of promise is essentially a faculty of memory that has the power to bring a body of people back to their beginning, that is, back to the moment when they agreed on an aim and a purpose. In this sense, the promise is a reminder that keeps on bonding the group together and linking the individual back to a past from which it began and from which it can begin again.”

“The promise,” Lemm continued, “exercises control over the future by means of drawing the future ever further into the past. In so doing, the promise reverses the flow of time. Thus, instead of being born into an uncertain future, one is born into a secured past.”

[I go on to talk about how promise relates to hope, but I’ll cut this off here. I hope this at least helps stimulate our thinking about how we relate to the future, especially now that so much may hinge on how we face what is to come.]

News and Resources

A few weeks ago, I cited Thomas de Zengotita’s work in my discussion of how the coronavirus resisted hyperreal mediation. It turns out I was onto something. Here’s an interview de Zengotita recently gave on the precisely this theme (my thanks to Zach Terrell for passing along the link):

“No matter how many charts they draw, no matter how many statistics they give you, no matter how good their predictions are, no matter what they show, cruise ships and hospitals, you can’t cover this … thing. It’s invisible and it’s everywhere.”In that interview, de Zengotita cited an essay he wrote in 2014 about why Google Glass (remember those) would ultimately fail. It remains an interesting piece for its discussion of screens:

“The screen is a meta-medium, which may be why it has so far eluded systematic treatment. It channels and filters other media. Speech and music, charts and maps, writing, pictures, film, video—the screen conveys them all. But the screen does have its own characteristics, its own meta-qualities. Above all, it displays. But, in displaying this, it hides that. Unknown treasures lurk perpetually just out of sight, clamoring sotto voce for your attention. What are you missing, at each moment, as the price of this display? Displaying, hiding—simultaneous effects constituting a quality for which there is as yet no word, but it is a quality that conditions the way we conceive and perceive of everything, the way we live now.”Chad Wellmon on what we can learn from Max Weber about the life of learning today:

“The most urgent questions concerned the forms for conducting a life and the character, habits and virtues that might sustain them. Intellectual work was spiritual work. Anyone seeking to craft a meaningful life engages in it. It is a task for all those who live in a disenchanted world in which meaning is not something that inheres in the world itself or that a job can simply provide, but rather is something to be asserted and made (and contested) by and among humans themselves.”“The Normal Economy Is Never Coming Back” by Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy:

“After the coronavirus pandemic, such pleas can only seem quaint. We now know what truly radical uncertainty looks like. A huge part of the world’s population has had the basic functioning of its life radically disrupted. None of us can confidently predict when we will be able to return to our pre-coronavirus lives. We may hope that things will “return to normal.” But how will we tell? After all, things seemed normal in January, just weeks before the world stopped. If radical uncertainty was a concern before, it will now be an ever present reality.Jason Farman has made the last chapter of his book, Delayed Response: The Art of Waiting from the Ancient to the Instant World, available online. From “Tactics for Waiting”:

“Waiting points to our desires and hopes for the future; and while that future may never arrive and our hopes may never be fulfilled, the act of reflecting on waiting teaches us about ourselves. The meaning of life isn’t deferred until that thing we hope for arrives; instead, in the moment of waiting, meaning is located in our ability to recognize the ways that such hopes define us.”“The French brotherhood burying the dead – rich or poor - since 1188”

Benjamin Bratton’s “18 Lessons of Quarantine Urbanism”:

“At this point, we are looking at months of extreme weirdness and grief and then things will return to a state that will feel more normal, but forever not the same normal. Right now, that is the optimistic scenario. Afterwards, many ways of doing things, ways of thinking, ways of getting things going and offering critiques, may just not come back. Some will be missed, others not even noticed. What are the important lessons to be learned before the normality that caused mayhem returns? A second wave of the virus would be catastrophic, but so would another wave of its underlying causes.”

Re-framings

— Blaise Pascal, Pensees:

“We do not rest satisfied with the present. We anticipate the future as too slow in coming, as if in order to hasten its course; or we recall the past, to stop its too rapid flight. So imprudent are we that we wander in the times which are not ours, and do not think of the only one which belongs to us; and so idle are we that we dream of those times which are no more, and thoughtlessly overlook that which alone exists. For the present is generally painful to us. We conceal it from our sight, because it troubles us; and if it be delightful to us, we regret to see it pass away. We try to sustain it by the future, and think of arranging matters which are not in our power, for a time which we have no certainty of reaching.

Let each one examine his thoughts, and he will find them all occupied with the past and the future. We scarcely ever think of the present; and if we think of it, it is only to take light from it to arrange the future. The present is never our end. The past and the present are our means; the future alone is our end. So we never live, but we hope to live; and, as we are always preparing to be happy, it is inevitable we should never be so.”

The Conversation

It’s clear that I’ve said enough in this installment, so let’s leave it at this: be well, be safe.

Cheers,

Michael

Thought provoking as always! My sense of the march of Modernity to where we are today is that Modernism was an intellectual and artistic movement that was stealthily co-opted by business and political interests to further their own ends. (What David Simpson is pointing out below). The World Fair still exists, but it has (d)evolved into the Consumer Electronics Show. This has changed the definition of futurism from a collective humanistic endeavor into a multitude of private for profit endeavors. Predictive technologies have nothing to offer the people, but are strictly commercial and political plays, so they are corporate futurism, a pseudo construct that is only a pale imitation of real futurism from, say, the Bauhaus or Buckminster Fuller.

The silver lining of the Pandemic is that we are able to see the ourselves and the stars while the lights are metaphorically out. As Leonard Cohen sang, 'there is a crack in everything, that's how the light gets in.' Humanity is not the Economy, and we are present with potential for change.

I haven’t finished your piece, but started watching the New York 1939 clip, and felt almost physically sick. It threw light for me on what CS Lewis was writing so passionately against in That Hideous Strength - the triumph of money, materialism, and the worship of technology and humanity’s “achievements”. And as fascist as anything that came out of Germany and Italy ( or to be fair, the Soviet Union)