“There is absolutely no inevitability as long as there is a willingness to contemplate what is happening.”

— Marshall McLuhan, The Medium is the Massage

This time around I’m passing along a slightly expanded and edited version of a short talk I had the pleasure of giving this morning at a virtual event hosted by the Future Narratives Lab based in the UK.

My thanks to Daniel Stanley for the invitation to participate alongside far more accomplished panelists, Dr. Jeannette Estruth, professor of history at Bard College, and Dr. Kanta Dihal, Senior Research Fellow at the Leverhulme Center for the Future of Intelligence at Cambridge University. They and Daniel gave terrific presentations, and when the recording is available I’ll pass it along. The theme of the event was “the narratives behind Big Tech,” and in my contribution I revisited some earlier work on the rhetoric of technological determinism.

The relationship between technology and narrative is long-standing. Indeed, some have argued that it is at the heart of human civilization.

It was once fashionable to characterize human beings as tool-using animals (although this turns out not to be the best way of getting at whatever might be distinctly human). It has also been suggested that we understand human beings as story-telling animals. Technology theorist N. Katherine Hayles has implicitly argued for a synthesis of these two positions by framing narratives as a technology for making meaning.

Hayles argued that “the primary purpose of narrative is to search for meaning, thus making narrative an essential technology for human beings, who,” she claims, “can arguably be defined as meaning-seeking animals.”

Historian of technology David E. Nye has also linked narrative and technology in a slightly different, but likewise intriguing manner:

“Composing a narrative and using a tool are not identical processes, but they have affinities,” Nye observed.

“Each requires the imagination of altered circumstances, and in each case beings must see themselves to be living in time. Making a tool immediately implies a succession of events in which one exercises some control over outcomes. Either to tell a story or to make a tool is to adopt an imaginary position outside immediate sensory experience. In each case, one imagines how present circumstances might be made different.”

“To link technology and narrative,” he adds, “does not yoke two disparate subjects; rather, it recalls an ancient relationship.” What’s more: “A tool always implies at least one small story. There is a situation; something needs doing.”

Nye argued that tools and narratives emerged symbiotically, as byproducts of a capacity to imagine what was not temporally encased in the present. He argued, too, that human culture depended on their emergence. In other words, tool making and storytelling are deeply related and integral to the human experience as we know it.

Not surprisingly, we use technology to tell stories, themselves a kind of tool as Hayles suggested, and we tell stories to sustain and direct our use of technology. To better understand our relationship to technology, then, it is certainly worth examining the stories we tell about our tools. Some of these narratives are of the grand variety: stories, for example, that aim to explain the underlying dynamics driving human history or the ostensibly distinctive features of a national culture. The Enlightenment myth of progress, comes to mind, or the myth of American ingenuity. Some narratives frame a particular class of technology, such as the mythos that surrounds the automobile in American culture. Then there are the more modest micro-narratives, which we weave around our own personal devices and tools. These stories order our relationship to technology as individuals and as a society.

Over the past several years, I’ve been especially interested in the role played by narratives of inevitability, that is to say, narratives that frame technological development as a deterministic process to which human beings have no choice but to adapt. I’ve sometimes called this the rhetoric of technological determinism.

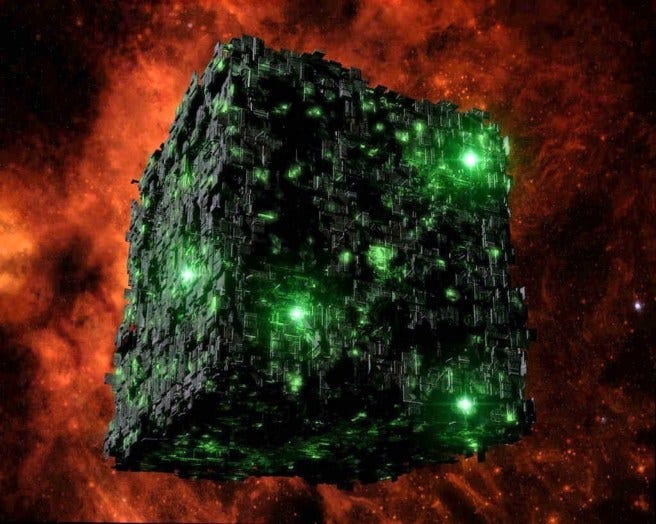

Several years ago I also coined a phrase that now strikes me as being rather less clever than then I imagined. With a nod to the Star Trek franchise, I began writing about those who deployed narratives of inevitability as suffering from a Borg Complex. I’m not especially well-versed in Star Trek lore, but it seemed to me that the Borg meme was popular enough to work as a catchy label for the rhetoric of technological determinism. You’ll remember that in the Star Trek universe the Borg are a hostile cybernetic alien race that announces to their victims some variation of the following: “We will add your biological and technological distinctiveness to our own. Resistance is futile.”

Resistance is futile. This seemed like a perfectly apt way to sum up the essence of the rhetoric of inevitability that was such a common feature of tech discourse.

I’ll give you a few of the examples that initially captured my attention.

Here is the notable American tech enthusiast, Kevin Kelly, on the question of automation a few years back:

“It may be hard to believe, but before the end of this century, 70 percent of today’s occupations will … be replaced by automation. Yes, dear reader, even you will have your job taken away by machines. In other words, robot replacement is just a matter of time.”

Kelly, incidentally, is probably a poster boy, if a rather amiable one, for the rhetoric of technological determinism. He wrote a book about tech trends actually titled The Inevitable.

Writing about ed tech in 2012, Nathan Harden claimed, “In fifty years, if not much sooner, half of the roughly 4,500 colleges and universities now operating in the United States will have ceased to exist. The technology driving this change is already at work, and nothing can stop it.”

A moments reflection will, of course, reveal that the trends Kelly and Harden claim to be merely announcing as inevitable outcomes are not merely matters of technical development and innovation. They are also functions of economic policies, legal structures, political power, and shifting cultural values.

Interestingly, around the time that I was first collecting examples of these stories of inevitability, Google was pushing its first iteration of Google Glass. Initially, it was widely touted as a transformative new technology. Gradually, however, it became clear that however many stories of inevitable adoption were told, Glass was not going to catch on.

At the time, the CEO of Evernote, Phil Libin, made the following claim in an interview with HuffPost:

“I’ve used [Google Glass] a little bit myself and—I’m making a firm prediction—in as little as three years from now I am not going to be looking out at the world with glasses that don’t have augmented information on them. It’s going to seem barbaric to not have that stuff.”

This firm prediction has not, as they say, aged well.

Glass is but one relatively recent and prominent example of tech touted as inevitable, which was anything but. As it happens, though, we tend to forget these examples. As historian Thomas Misa has written,

“we lack a full picture of the technological alternatives that once existed as well as knowledge and understanding of the decision-making processes that winnowed them down. We see only the results and assume, understandably but in error, that there was no other path to the present. Yet it is a truism that the victors write the history, in technology as in war, and the technological ‘paths not taken’ are often suppressed or ignored.”

Naturally, most of the examples I’ve collected over the years come out of my own US context, but narratives of inevitability are widespread. I’ll note, for the UK audience, one example from a 2017 report prepared by a Conservative MP presenting the case for a tech friendly government policy. “It is impossible to resist the rise of the machines,” the report concludes, “so we must let them lift us towards a Global Britain that uses the Fourth Industrial Revolution as a springboard to a more productive, outward-looking economy.”

You may have already noticed the prevalence of this rhetoric of inevitability. In more recent years, it’s often framed public debates about autonomous vehicles and surveillance technologies.

It’s worth noting, that narratives of inevitability come in all manner of temperamental variations, ranging from the cheery to the embittered. There is also variation regarding the envisioned future, which ranges from utopian to dystopian. And there are different degrees of zeal as well, ranging from resignation to militancy. Basically, this means that the rhetoric of inevitability may manifest itself in someone who thinks resistance is futile and is pissed about it, indifferently resigned to it, evangelistically thrilled by it, or some other combination of these options.

The sources of these narratives also vary. They may stem from a philosophical commitment to technological determinism, the idea that technology drives history. This philosophical commitment to technological determinism may also at times be mingled with a quasi-religious faith in the envisioned techno-upotian future. The quasi-religious form can be particularly pernicious since it understands resistance to be heretical and immoral. Painting with a decidedly broad brush, the Enlightenment, in this reading, did not, as it turns out, vanquish Religion, driving it far from the pure realms of Science and Technology. In fact, to the degree that the radical Enlightenment’s assault on religious faith was successful, it empowered the religion of technology. To put this another way, the notions of Providence, the Kingdom of God, and Grace were transmuted into Progress, Utopia, and Technology respectively. If the Kingdom of God had been understood as a transcendent goal achieved with the aid of divine grace within the context of the providentially ordered unfolding of human history, it became a Utopian vision, a heaven on earth, achieved by the ministrations Science and Technology within the context of Progress, an inexorable force driving history toward its Utopian consummation. It’s worth noting that stories of technological inevitability tend to flourish in contexts were the cultural ground has been prepared by linear and teleological understandings of history.

Of course, narratives of inevitability most often arise from a far more banal source: self-interest, usually of the crassly commercial variety. All assertions of inevitability have agendas, and narratives of technological inevitability provide convenient cover for tech companies to secure their desired ends, minimize resistance, and convince consumers that they are buying into a necessary, if not necessarily desirable future.

Recently, Margaret Heffernan succinctly summed up the underlying message of Big Tech’s rhetoric of inevitability in a personal and eloquent reflection on the theme: “The future might not have happened yet, but it was already decided.” “The goal,” as she put it, “isn’t participation, but submission.”

Once again resistance is futile. One either gets on board or gets left behind.

Narratives of inevitability have the effect of foreclosing thought and deliberation. If outcomes are inevitable, then there’s nothing to do but assimilate to this pre-determined future, to go along for the ride prepared for us whatever the consequences. As Lauren Collee has recently put it, “Techno-determinist futures … are used to habituate us to the present.” And, specifically, to the present designs of tech companies.

The truth, of course, is more complicated. As historians of technology have demonstrated, historical contingencies abound and there are always choices to be made. The appearance of inevitability is a trick played by our tendency to make a neat story out of the past and project it onto the future. And this tendency is one that tech companies are clearly prepared to exploit.

So, to sum up, beware narratives of technological inevitability. Resistance, if it be necessary, is not necessarily futile, and, as Heffernan reminds us, “Anyone claiming to know the future is just trying to own it.”

News and Resources

From historian Leo Marx’s “Technology: The Emergence of a Hazardous Concept”:

“We have made [‘technology’] an all-purpose agent of change. As compared with other means of reaching our social goals, the technological has come to seem the most feasible, practical, and economically viable. It relieves the citizenry of onerous decision-making obligations and intensifies their gathering sense of political impotence. The popular belief in technology as a—if not the—primary force shaping the future is matched by our increasing reliance on instrumental standards of judgment, and a corresponding neglect of moral and political standards, in making judgments about the direction of society. To expose the hazards embodied in this pivotal concept is a vital responsibility of historians of technology.”Craig Mod on why “looking closely is everything”:

“This act of ‘really looking’ is deceptive. It requires an almost ‘unlooking’ to see closely, a kind of defocusing. Because: We tend to see in groups, not details. We scan an image or scene for the gist, but miss a richness of particulars. I suspect this has only gotten worse in recent years as our Daily Processed Information density has increased, causing us to engage less rigorously — we listen to podcasts on 2x speed or watch YouTube videos with a finger on the arrow-keys to fast-foward through any moment of lesser tension. Which means we need all the help we can get to prod ourselves to look more closely, and a good description can help do just that.”A terrific 2018 essay by Shannon Mattern, “Maintenance and Care”:

“What we really need to study is how the world gets put back together. I’m not talking about the election of new officials or the release of new technologies, but rather the everyday work of maintenance, caretaking, and repair.”Siobhan Lyons on “The Compatibility Trap”:

“The trajectory of technological evolution often seems, in hindsight, to be inevitable, and this is certainly what technological determinists believe. But to accept such a vision of the future is to abet a self-fulfilling prophecy that enables big tech companies to proceed with impunity.”

Which is to say, resistance is not futile even if it can be costly.Consuming media is as much about managing feeling as accessing information:

“And yet, for all of this comforting control, it can never be enough. The more one unthinkingly pursues joyful enclosure, the more exquisitely sensitive one becomes to discomfiting inputs, whether sensory or ideological. Over time, you need to turn up the white noise a little louder to avoid distraction and soon the thought of sleeping without a media pillow becomes impossible.”Great essay in The New Atlantis from Adam Elkus, whose work I frequently cite here, “Welcoming Our New Robot Overlords”:

“As our lives become more and more dependent on online platforms — especially during a pandemic that limits our in-person communication — the stakes in giving the machines control over our speech and behavior are higher than ever. We have delegated this power to them such that they can protect us from all-too-real harms and safeguard certain liberties, with the assumption that they act in accordance with our fundamental values. But do they really?”Dan Nixon beat me to it (from 2018), “Attention is not a resource but a way of being alive to the world”:

“However, conceiving of attention as a resource misses the fact that attention is not just useful. It’s more fundamental than that: attention is what joins us with the outside world. ‘Instrumentally’ attending is important, sure. But we also have the capacity to attend in a more ‘exploratory’ way: to be truly open to whatever we find before us, without any particular agenda.”

Nixon’s essay reminded me of an earlier essay I’d written on attention in which I was tried to differentiate among different modes of attending to the world, “Spectrum of Attention.”Recalling the installment a few weeks ago about the loss of the night sky, here is a beautiful photo essay in Emergence Magazine: “Dark Skies.” Relatedly, a recent study suggests the problem may be worse than I realized: “Study finds nowhere on Earth is safe from satellite light pollution.”

“Fold ‘N Fly,” devoted to the art of paper airplanes.

Lecture by Eric McLuhan, Marshall’s son: “Media Ecology in the 21st Century.”

Re-framings

— From the opening of an excerpt published a few years back from Evgeny Morozov’s To Save Everything, Click Here:

There are many awful ways to respond to technological change, but succumbing to technological defeatism is certainly one of the worst. Technological defeatism—a belief that, since a given technology is here to stay, there’s nothing we can do about it other than get on with it and simply adjust our norms—is a persistent feature of social thought about technology. We’ll come to pay for it very dearly.

Technology pundit Kevin Kelly exhibits this defeatist mindset when he writes that “we can choose to modify our legal and political and economic assumptions to meet the ordained [technological] trajectories ahead. But we cannot escape from them.” According to such defeatist views, the world works very much like it was described in the motto of Chicago’s 1933 World’s Fair: “Science Finds—Industry Applies—Man Conforms.”

The reasons to oppose technology defeatism are simple: It downplays the utility of resistance and conceals the avenues for seeking reform and change. As a result of technological defeatism, concerns and anxieties about various technologies are recast as reactive fears and phobias, as irrelevant moral panics that will quickly fade away once users develop the appropriate coping strategies and upgrade their norms. But is anxiety about technological change such a bad thing? And does it always imply technophobia?

— Ursula Franklin from her 1989 Massey Lectures, “The Real World of Technology”:

I think what we are all discussing are political issues. They are political in the best sense of the word, in the original Greek sense of the word, in that they affect the community, the very citizens who have to work and live together. When all the technology is disposed of, when we have understood or put aside all the details, what is left are the issues of how people live together. These political issues have existed ever since people have lived together and were articulate about their relationships.

To me, it is important to understand that technology is practice, it is the way we do things around here. This definition takes machines and devices into account, as well as social structures, command, control, and infrastructures. It is helpful for me to remember that technology is practice. Technology, as a practice, means not only that new tools change, but also that we can change the practice. If we have the political will to do so, we can set certain tools aside, just as the world has set slavery and other tools aside. It is also the nature of modern technology that it is a system. One cannot change one thing without changing or affecting many others.

The Conversation

It’s been a while since I’ve had any outside publications to tell you about, but that may be changing in the near future. I’m currently working on a piece on Illich for The New Atlantis, and some other projects are in early stages.

Also, I recently enjoyed talking to Geoff Shullenberger about the virtues of the older tech critics I write about on here all the time. You can listen here.

Almost exactly a year to the day, I published an installment on Zoom fatigue as we were settling in to life in Covid times. That post remains the most popular thing I’ve written. Happily, it now seems as if we might be able to begin moving mostly out of Zoom Land in the coming weeks and months.

Hope you all are well. And, as always, thanks for reading and sharing the newsletter.

Cheers,

Michael

The techno-determinism you write about is something I’m keenly aware of here in Vermont. We’re a mostly rural state, but there is almost universal support for bringing high-speed internet into every home. Among the urban transplants this makes a sort of sense, since they tend to move here for the slower pace and land-based way of life, then immediately try to transform it into the place they just escaped. But there’s a surprising amount of support from those who grew up here, because they have accepted the idea that a decent future for their children has nothing to do with that land-based way of life, and everything to do with technologies few of them really understand. Needless to say, state government is fully behind this techno-fatalism, and will be using the windfall from the federal government's covid stimulus to make the state even more dependent on those technologies.

Regarding the roots of utopian or progressive determinism, this is often blamed on a variety of Christian heresies including Calvinism or species of it, at least from the medieval perspective. Voegelin and Jonas dug into that. I wonder if it is any escape from the problem to imagine there is a correct tradition in intellectual history for thinking properly about history. Maybe it is only good or bad to be pessimistic or optimistic to the extent it helps us cope with actual circumstances.

I wonder if you’ve considered Barth as a relevant critic on this topic. He has strong words in Church Dogmatics against providentialism that might be better classified as a type if Hegelian historicism. If secularized protestant progressivism led to Hegel, Hegel also fed the right or centre-right alt modernism of Kuyper and European Christian Democrats, who might be understood as wanting to have the blessings and promises of technocapitalist modernity and consecrate them too. More reactionary antimodernist or integralist political theologies look comparatively less naive. But would I rather be a young Arendt growing up in Lisbon or Amsterdam? Whose optimism or pessimism we are caught up in may be most decisive.