The Iowa caucus affair last night was a masterclass in hyperreality.

The relevant facts are as follows. It was the long-anticipated kickoff to the primary season in an ever-expanding election cycle that now seems more or less co-terminous with the president’s four-year term. Iowa has an outsized place in this process, as it traditionally holds the first-in-the-nation caucus. Last night, under intense media scrutiny and pressure for immediate results, a complex system buckled, a new app made everything worse, results were withheld, and a collective meltdown ensued.

There are currently any number of accounts of what exactly happened, who was to blame, and what this will mean for the candidates and their campaigns. I will link to none of it because, frankly, none of it matters.

What matters, in my view, is that this whole affair illustrates the deep disorders of our hyperreal political culture, indeed of the all-encompassing hyperreality within which we move and breathe and have our being.

Let’s start with this, a take that became increasingly common through the evening and which I continued to hear reiterated this morning.

Mr. Levitz and those who have echoed this sentiment, inadvertently disclosed a fundamental truth about the situation: basically, the Iowa caucus was a pseudo-event.

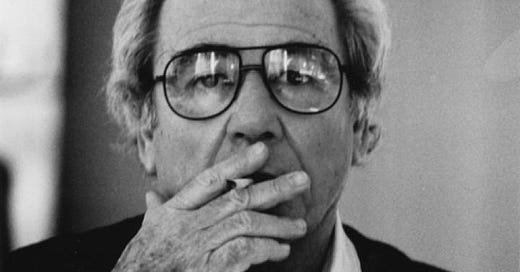

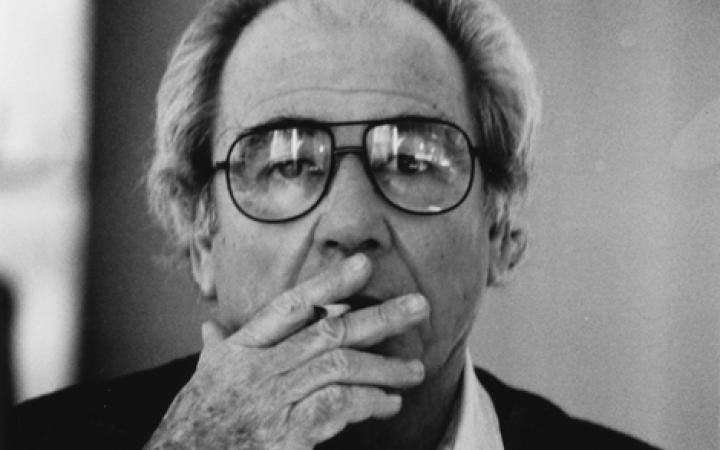

You may remember that it was the American historian Daniel Boorstin, who coined the term in his 1962 book, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-events in America.

“A pseudo‑event, then,” he explained, “is a happening that possesses the following characteristics:

(1) It is not spontaneous, but comes about because someone has planned, planted, or incited it.

(2) It is planted primarily (not always exclusively) for the immediate purpose of being reported or reproduced.

(3) Its relation to the underlying reality of the situation is ambiguous.

(4) Usually it is intended to be a self‑fulfilling prophecy.

Boorstin also gave us the expression “famous for being famous,” which is about as apt a summation of the ontology of pseudo-events as you’re likely to find.

The tacit admission in the tweet above is that the Iowa caucus matters mostly as a pseudo-event, that is in being talked about and that for an increasingly short window of time—maybe one morning’s news cycle … maybe. Without that, what good is it?

Which is why the mishaps last night were so costly. It was not simply that our eventual knowledge of the “real” results was in jeopardy—although there may be something to that, too—but, more importantly, it’s that the value of the event in the economy of the hyperreal was threatened, and its hyperreal value was what mattered most.

Hence, the discussion quickly became one of saving some of that value and the obvious way to do that was simply to get on with a speech claiming victory of some sort and getting air time for it, which several of the candidates proceeded to do. Then, of course, the dynamics of the pseudo-event kicked in again as participants argued over whose speech was covered appropriately, etc. It’s worthing noting that the hyperreal environment exists chiefly for its own sake. While some may be more adept at co-opting certain of its forces, it finally exists for itself.

This is why James Gleick’s tweet here misses the point.

Yes, he’s right, that assumption is not warranted. We don’t need to know immediately and the desire for immediacy is part of the problem, but that no longer matters. It hasn’t mattered for years. In the currently-existing media-political environment, waiting a day or a week is unthinkable.

As I put it in my own contribution to the unfolding hyperreal moment: It's not so much an attention economy as it is an economy of care. Tomorrow, no one will care. The habit of immediacy atrophies the capacity to extend care toward the past or the future.

Digital media renders the present a black hole, everything is sucked into it: the past and the future, as well as our emotional and cognitive resources. Or, as Alan Jacobs, drawing on Thomas Pynchon has put it, it collapses our “temporal bandwidth.”

To be clear and draw this dispatch to a close, it’s not that the Iowa caucus debacle was somehow unique or distinctive. Rather, it was a moment of clarity, it was, in the literal sense, apocalyptic, a pulling back of the veil. The failure of the system, the glitch, disclosed something about the nature of our everyday reality, to which we grow increasingly numb even as we are exhausted by it. Indeed, the failure is our best chance to grasp the true nature of our situation.

So while my first instinct was to label the whole mess a pseudo-event, the less flip, more disconcerting reality is that labeling something a pseudo-event was reassuring because it assumed our ability to identify "real"-events. The role of the obviously fantastical is to reassure us of the reality of our ordinary experience. Presently, that distinction is tenuous at best. Who can draw the line? What part of the proceedings last night can one deem real as opposed to fake or artificial? What aspect wasn’t already shot through with qualities of a pseudo-event or overlaid with the textures of hyperreality?

As the author Tim Maughan recently tweeted, “everybody got excited about postmodernism, nobody was ready for postmodernity.” That seems about right.

This is a Dispatch from The Convivial Society. Ordinarily these go out to paying subscribers and supplement the main newsletter, which is freely available to all. If you’d like to get these periodic dispatches, you can subscribe through the link below (if you’re here for the first time, you can subscribe to the free newsletter through the same link). Also feel free to share however you like. Alternatively, do neither and carry on.