The Convivial Society, No. 22

"I believe that this crisis is rooted in a major twofold experiment which has failed, and I claim that the resolution of the crisis begins with a recognition of the failure. For a hundred years we have tried to make machines work for men and to school men for life in their service. Now it turns out that machines do not 'work' and that people cannot be schooled for a life at the service of machines. The hypothesis on which the experiment was built must now be discarded. The hypothesis was that machines can replace slaves. The evidence shows that, used for this purpose, machines enslave men." — Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality

Neil Stephenson was recently interviewed on Tyler Cowen's podcast. I'm not necessarily commending the interview to you, there's some odd stuff in there, including a casual claim, made in passing, that the simulation theory of the universe is just like the medieval cosmological argument, which is ... not at all the case. He must have had Berkley in mind (sorry). Nonetheless, I will take the following from Stephenson as a point of departure for a few observations:

"Our civil institutions were founded upon an assumption that people would be able to agree on what reality is, agree on facts, and that they would then make rational, good-faith decisions based on that. They might disagree as to how to interpret those facts or what their political philosophy was, but it was all founded on a shared understanding of reality.

And that’s now been dissolved out from under us, and we don’t have a mechanism to address that problem."

What they are discussing, of course, are the corrosive effects of digital media, although they frame it more narrowly as a "worst case scenario" involving social media. Social media is one particular shape that digital media takes, but I think it is important that we understand them as merely a subset of the greater digital whole. In any case, when pressed by Cowen, who along the way assumes a "what's so bad about this" posture, regarding the precise cause of the situation, Stephenson points to the algorithmically driven nature of social media. "It’s very easy," he adds,

for people who are acting in bad faith to game that system and produce whatever kind of depiction of reality best suits them. Sometimes that may be something that drives people in a particular direction politically, but there’s also just a completely nihilistic, let-it-all-burn kind of approach that some of these actors are taking, which is just to destroy people’s faith in any kind of information and create a kind of gridlock in which nobody can agree on anything."

He then gestures toward a 2003 book, A Culture of Fact by Barbara Shapiro, which examines the origins, in the social milieu of the early modern English legal system, of the idea of a fact. Stephenson glosses the thesis of the book as follows:

"Procedures were developed that would enable people to agree on what was factual, and that had a huge impact on culture and on the economy and everything else.

And now that’s, as I said, going away, and the only way to bring it back is, first, to have a situation where people need and want to agree on facts."

Narrator: There is no way to bring it back.

The gesture toward the early modern context for the emergence of "facts" is instructive, and it's important to see that certain features of our current crisis have deep roots in the culture of modernity. In one sense, what we are experiencing is not altogether unlike what Europe experienced as it transitioned from late medieval to early modern social structures, a transition that was driven, in large measure but not exclusively, by the advent of moveable type printing, or the mechanization of the word.

One characteristic of that tumultuous period was a heightened experience of epistemic pluralism, chiefly owing to the collapse of what we might, for the sake of convenience, term the "medieval synthesis," a world picture that rendered experience more or less coherent and meaningful, as any such world picture tends to do. In light of this, the challenge of the early modern period was, as Shapiro's work suggests, to reconstitute something like an epistemic consensus on which to rebuild society—to generate a new world picture. Except that the challenge was answered with a bit of a dodge, which was to construct a normative "view from nowhere." The trick was to bracket certain kinds of truth claims from the public sphere, those we might think of as theological or metaphysical or otherwise narrowly sectarian, while allowing only those claims that were objectively derived from an unbiased consideration of presumably neutral ... facts. Simultaneously, legal, political, and educational structures were developed to reinforce this privileging of the uninterpreted fact. Think of the development of these structures and institutions as the mechanization of politics. The new world picture, as it turned out, consciously and unconsciously drew on the machine as an organizing principle. The answer to the cultural upheavals, then, was to build institutions that would generate consensus not through the arduous work of contesting and resolving differences, but by automating the public realm and cultivating subjects qua citizens that would be willing to buy into the validity of "objective facts," neutral institutions, etc.

In short, modernity was built upon a myth: the myth of neutrality or objectivity—neutral facts, neutral procedures, neutral institutions, neutral technology. It was this myth, wielded as a weapon against all manner of superstitions, that sustained the ideals of "Reason," "Progress," the "Rational Actor," etc. Reader: It, too, was a superstition.

One way of understanding our moment, then, is to recognize that digital technology, which is to say the scale and patterns of human interaction it makes possible, disabuses us of the myth, which, of course, always had its detractors. Consequently, we are living through a period of profound crisis, deeper than most of us realize, or so it seems to me on most days, and simple appeals to conventions and solutions grounded in the old myth now ring hollow. The old virtues and ideals, as well as the institutions they sustained, have lost their purchase on the imagination. They have, if you will, lost their "self-evident" character. What had been first principles upon which arguments were built, have themselves become things to be argued about. Like the early moderns, our regnant world-picture has shattered and we are casting about for new ways of building consensus, new ways of coping with the challenges of epistemic pluralism, new ways of ordering society toward the common good. Looked at from a certain perspective, we might see this as a hopeful moment, full of promise and opportunity. However, given the way I understand how media structure without necessarily determining the possible paths along which we may travel, I'm not altogether sanguine about what lies immediately before us.

[N.B. I, too, cringe at the generalities I dispensed above, nonetheless ... ]

______________________________

Relatedly, from the blog, Technological Enchantments and the End of Modernity.

News and Resources

Via Robin Sloan's newsletter, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing's "On Non-Scalability: The Living World Is Not Amenable to Precision-Nested Scales."

Jonathan Zittrain on the "hidden costs of automation." Zittrain's closing paragraph: "Perhaps all this technology will work—and that, in turn, will be a problem. Much of the timely criticism of artificial intelligence has rightly focussed on the ways in which it can go wrong: it can create or replicate bias; it can make mistakes; it can be put to evil ends. We should also worry, though, about what will happen when A.I. gets it right."

This recalled an old post: "Accidents and disasters get our attention, their possibility makes us anxious. The more spectacular the promise of a new technology, the more nervous we might be about what could go wrong. But, if we are focused exclusively on the accident, we lose sight of the fact that the most consequential technologies are usually those that end up working. They are the ones that reorder our lives, reframe our experience, restructure our social lives, recalibrate our sense of time and place. Etc."MIT's Media Lab founded by Nicholas Negroponte in 1985, had been directed by Joichi Ito until his resignation Saturday following the cascading revelations about the Lab's connections to Jeffery Epstein. Evgeny Morozov and Kate Darling have written incisively about the debacle.

In 2012, Will Boisvert wrote a scathingly critical essay on the work of the Media Lab. It's worth revisiting, chiefly to be reminded of the banality of so much of what passes for innovation. The closing paragraph:

"There was a time when machines had a grandeur and glamour in their own right, when steamships, airplanes, cars, and dynamos were astonishing innovations that accomplished inhuman feats. Back then, we did not expect machines to be us; they were bigger and stronger and faster than us, and we revered them as they remade the world in ways we had never imagined. That heroic Machine Age ended when the Saturn V rocket, greatest of machines, took us all the way to the moon, and what did we do? We hit some golf balls and went home. Now machines can aspire to nothing but mundane servility, catering to our whims, reflecting our dull fantasies back at us. They take us nowhere except into our own heads."

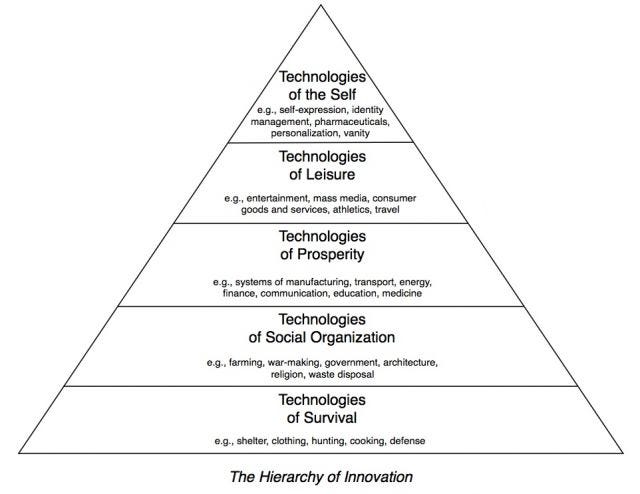

Boisvert's piece recalled to mind a post by Nick Carr, also from 2012, proposing a Maslovian hierarchy of innovation.

Writing for RAND in 1998, James Dewar explored the parallels between "the Information Age and the Printing Press." He concluded, "However, the strength of the parallels does suggest that: 1) networked computers could produce profound cultural changes in our time, 2) unintended consequences are not only possible but likely to upset conventional extrapolations of current trends (or even historical parallels), and 3) the changes could take decades to see clearly." 1) Check. 2) Check. 3) Check.

The Pentagon is testing mass surveillance balloons. Relatedly, "satellite imagery is improving in a way that investors and businesses will inevitably want to exploit."

Charles Rubin reviewsMastery of Nature: Promises and Prospects, edited by Svetozar Y. Minkov and Bernhardt L. Trout.

New techniques for examining ancient palimpsests reveal writing in long-dead languages on manuscripts kept at St. Catherine's monastery in Egypt, home to the world's oldest continuously working library. The monastery was founded c. 550 AD. In all likelihood, there were people alive then who were alive when Rome fell in 476. This same place is still doing today what it was founded to do then, which is remarkable to consider. The manuscripts have been digitized and are available at the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library.

When I was in school, I learned that the first inhabitants of the Americas made their way across a land bridge over what is now the Bering Straights. This is no longer the scholarly consensus.

Re-framings

When I was working on the dissertation that never materialized, I stumbled upon the transcript of a roundtable discussion among participants in a 1972 conference on Hannah Arendt's work. Arendt herself was a participant, as was Hans Jonas. Here is an excerpt of a portion of an exchange between the two of them that I recently revisited. Jonas argues that in the absence of ultimate values to guide our increasingly promethean technological capacities, we proceed from a Socratic acknowledge of our ignorance and hence with an abundance of caution and humility, i.e. anything but "move fast and break things." You can read a bit more of the exchange here.

____________________

From George Steiner's Real Presences:

"To learn by heart is to afford the text or music an indwelling clarity and life-force. Ben Jonson’s term, 'ingestion', is precisely right. What we know by heart becomes an agency in our consciousness, a 'pace-maker' in the growth and vital complication of our identity. No exegesis or criticism from without can so directly incorporate within us the formal means, the principles of executive organization of a semantic fact, be it verbal or musical. Accurate recollection and resort in remembrance not only deepen our grasp of the work: they generate a shaping reciprocity between ourselves and that which the heart knows. As we change, so does the informing context of the internalized poem or sonata. In turn, remembrance becomes recognition and discovery (to re-cognize is to know anew). The archaic Greek belief that memory is the mother of the Muses expresses a fundamental insight into the nature of the arts and of the mind.

The issues here are political and social in the strongest sense. A cultivation of trained, shared remembrance sets a society in natural touch with its own past. What matters even more, it safeguards the core of individuality. What is committed to memory and susceptible of recall constitutes the ballast of the self. The pressures of political exaction, the detergent tide of social conformity, cannot tear it from us. In solitude, public or private, the poem remembered, the score played inside us, are the custodians and remembrancers (another somewhat archaic designation on which my argument will draw) of what is resistant, of what must be kept inviolate in our psyche."

Recently Published

Haven't had much to report of late, but here's a short post on the moral use of Twitter and a stack of books that will double as a teaser for a piece that will be forthcoming later this fall.

Trust you all are well. I'm at the point of the year, here in Florida, when I scan the 10-day forecast each morning for the first day the low will break below 70°. Regrettably, it is not yet in view. If you've already tasted autumn, enjoy it on my behalf.

Cheers,

Michael