Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter about technology and culture, both understood broadly. I had been working on another essay titled “Secularization Comes for the Religion of Technology,” and I mentioned in a couple of places that it was on its way. That piece is almost ready, but I found myself over the past few days wanting to say a few things about Apple’s mixed reality headset, Vision Pro, which became available last week. So that’s what you have here. The secularization of the religion of technology piece will be out next week. I trust you are all well. As always, welcome to new subscribers, glad you made your way here.

Here’s an analogy for your consideration. Just as physical density bends time, so does information density bend the experience of time. (Disclaimer: I’m not a physicist and don’t pretend to understand general relativity.) What I’m trying to get at with this possibly suspect analogy is that when digital media compresses the amount of information we encounter during a given period of time, which is what I mean by information density, our sense of the passage of time gets weird. How long ago did something happen? What happened yesterday for that matter? In what order did a set of events happen? Are we just getting collectively worse at judging such matters? I’m not inclined to think so. Instead, I’d argue that this is an effect of information density in digital media environments, or, as it has been said, the medium is the message.

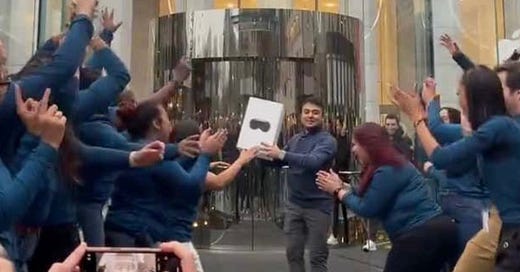

That was, I admit, an inordinately elaborate way of getting to the point: Apple released Vision Pro just a week ago, and I feel as if it might as well have been a year ago. I suspect many of you reading this will already have encountered a flood of reviews and analyses of Apple’s new mixed reality headset. Some of you may have seen one in the wild. Some of you may even have procured Vision Pro for yourselves. If so, I hope that you, too, enjoyed the kind of raucous celebration that this guy got at an Apple Store when he emerged as the first customer to have bought the $3,500 headset.

And [clears throat] if you did, in fact, drop $3,500 on Vision Pro, I hope that you will also remember your lowly newsletter-writing friend and become a patron of his humble efforts. More seriously, feel free to be in touch with observations about your own experience thus far with the device.

Long-suffering readers will remember that when Apple first announced Vision Pro at its developer’s conference last summer, I wrote a brief reflection suggesting that the “worst thing about the age of digital media will turn out to be how hard it became to look one another in the eyes.” Unless, of course, we’re talking about the virtual representation of your eyes that Vision Pro projects on its surface whenever you feel compelled to wear the headset while casually talking to another person on the couch as in the image below from Apple’s website.

I think that point is still worth making, while, of course, recognizing that most of us have found far more inexpensive ways to scatter our attention and presence. This time around, though, I have a few additional thoughts for you to consider.

Recently, a tweet (or post or whatever we call them now) came across my timeline showing a selfie taken by a father holding a sleeping infant while wearing Vision Pro. The father described it as “dad mode” and referred to discovering a great application for the device.

I hesitate to include the image here, in part, because I have no interest in even appearing to shame a parent about their tech use. But I do think it can be clarifying to reflect on this case, and the reaction it elicited, for just a moment. If you care to take a look, here you go.

First, responses to the image in the comments and quote-tweets were pretty animated but also seemed rather evenly split between the critical and the supportive. But, whether critical or supportive, they were heated. Granted, social media comments obviously have a tendency to come in hot, so I’m wary of reading too much into this. But, they did call to mind a paragraph from Wendell Berry that I had recently revisited. In his 2000 critique of sociobiology, Life is a Miracle, Berry wrote, “It is easy for me to imagine that the next great division of the world will be between people who wish to live as creatures and people who wish to live as machines.”

When sociologist James Hunter popularized the term “culture wars” in a 1991 book by the same title, he noted that the culture wars were longstanding, but that the traditional battle lines were being redrawn with older coalitions breaking up and giving way to new ones. In 2000, Berry was predicting a similar realignment. As I survey the terrain today—in a decidedly un-scientific fashion, of course—I think we can see a new front opening up in the culture war precisely along the lines Berry foresaw and scrambling existing alignments and coalitions.1 And how somebody feels about a dad holding an infant while wearing Vision Pro might be a good indicator of what side of that emerging conflict they’re likely to find themselves on.

Now, if you were to ask me what exactly living as a creature (as opposed to a machine) entailed, well, I think I’d invite you to join me for a drink and a long, leisurely conversation. If you pressed me for a more immediate answer, I’d suggest that living as a creature involves a humble (but also joyful) embrace of the limitations of our embodied human condition.

So, for example, when Berry writes about the division between those who wish to live as creatures and those who wish to live as machines, he also warns against a willingness to allow machines and the idea of the machine to set the standard for how creatures ought to live. In certain contexts, machines can operate at a pace, scale, precision, and intensity with which creatures cannot compete. When machine-like consistency, efficiency, speed, or production is demanded of creatures, then creatures are made to live as if they were machines.2 This never ends well for creatures, including human creatures. Most people know this, it’s just that some see this as cause to transcend the human and others see it as cause to re-imagine the human-built world.

But while such machine-like behavior is often coerced, it is also often embraced willingly, although, of course, such willingness is, in part, the product of a process of formation to which most of us are subject from birth. We have been schooled by dominant social structures to presume that the limitations inherent in our embodiment are merely obstacles to be overcome rather than the parameters within which meaningful, satisfying, and purposeful lives might unfold. Cultural and economic forces work in tandem to encourage a pathological dissatisfaction with our condition, a dissatisfaction which is in turn harnessed to fuel the engines of commercial and institutional growth. For what lack are we tempted to feel which will not also be remedied by the wares of the market or the services of an institution?

Now, let me put all of this another way. I could just as easily say that living as a creature is not merely about the embrace of limitations, which makes the whole business out to be a rather joyless act of resignation, but rather about the almost inexhaustible depths of experience available to us when we strive for a fullness of presence before the world by embracing the primacy of the body’s entanglement with its immediate surroundings to human experience.

Consider again the father holding his sleeping infant on his chest. Forget for a moment all of the technological artifacts that might enter into that scene: the VR goggles, the smartphone, the television, the book, etc. The point is to imagine, to the degree that we are able, the depths of experience available to him if he were to seek a fullness of presence in that moment.

What does sight disclose, at first glance and after sustained attention? What details reveal themselves—about the texture of the skin, the features of the face, the fuzz of hair about the head? What scent does he pick up? Quite possibly it is unpleasant! But not always. It is likely to be subtle but distinct. What does he hear? The quiet breathing? What does he feel? The weight on his chest? The softness of the skin? On and on it goes. Now consider how such an experience might shape memory, self-reflection, affection, a sense of purpose and moral responsibility, etc. What if we, by whatever means, habitually denied ourselves such experiences of depth and fullness?

I know. I know. If you are a parent, you know how hard it is to be this attentive all the time. The likely outcome of any attempt to cycle through your senses in this way will be falling fast asleep before you get very far. My point is not that we must always practice this fullness of presence or that we should feel guilty whenever we fail to achieve it. My point is only that we should try sometimes to practice this fullness of presence—that I ought to do it more than I manage to. (I’ll let you judge the “ought” that applies to you.) And, of course, that we should do this in all manner of circumstances. The case of the parent holding a sleeping infant is emotionally charged and already laden with sentimentality. But all manner of mundane realities will bear this kind of attention and reward us with an altogether surprising depth of experience, beauty, and meaning. We have only to learn to see and hear and smell and taste and touch as we are able—to feel our way through the world with patience and care. And, who knows, the practice may yield a habit and the habit a characteristic way of inhabiting the world.

We might find, too, a renewed experience of community and friendship. C. S. Lewis, in writing about friendship, noted that lovers are absorbed in each other’s gaze, friends however are bound by a looking, not at each other, but in the same direction, which implies a common world or a common task or common loves. The image suggests that if we have no common world to look toward together, if we are captivated by our own private virtual worlds, friendship falters.

In The Enchantment of Modern Life, political theorist Jane Bennett argued that “the contemporary world retains the power to enchant humans and that humans can cultivate themselves so as to experience more of that effect.” “To be enchanted,” she wrote, “is to be struck and shaken by the extraordinary that lives amid the familiar and everyday.”

“Enchantment is something that we encounter, that hits us,” Bennett added, “but it is also a comportment that can be fostered through deliberate strategies.” Among those strategies, Bennett includes “honing sensory receptivity to the marvelous specificity of things.” I think she is exactly right about this. While I wouldn’t ordinarily use the term “enchantment” to describe such a comportment or way of being in the world, it does suggest a useful line of analysis.

The allure of digital technologies such as Vision Pro can be usefully framed, in part, as the pursuit of an alternative (re-)enchantment: virtual projections overlapping and obscuring our shared world, summoned and manipulated by gesture, sight, and speech as if the user were a wizard in a world responsive their command. It presents as magical.

But what if, as Bennett suggests, the world is already enchanted and the real alchemy that summons the miracle of being is that fusion of time and care that we call attention?

When I learn to live as a machine—by choice or otherwise—I become increasingly incapable of attending to the world. This might be because I am simply moving through life at a pace that prevents me from properly attending to the world. Or because I am striving for efficiency or productivity in realms of experience where those aims are, in fact, counter-productive. Perhaps it’s because I’m unable to resist the temptation to always be elsewhere than where I stand. Maybe it’s because I’ve placed $3500 goggles on my face. “A headset is a pair of spectacles, but a headset is also a blindfold,” as Ian Bogost recently put it. I think Berry would say that these can all be ways of conforming to life as a machine rather than as a creature.

Unable, then, to see the world because I have forgotten the way of being in the world that enables vision in the deepest sense, I can then be convinced of the superiority of virtual worlds.3 Increasingly captivated by virtual worlds, I am less likely to demand anything more or better. The tools that diminish my capacity to experience the world in full simultaneously promise to give me a better-than-real world.

Writing in 2001, Bennett wondered “whether the very characterization of the world as disenchanted ignores and then discourages affective attachment to the world.” Perhaps. The more pressing concern now is whether a growing enthrallment to devices that capture our attention precludes an affective attachment to the world (and, as Bennett feared, our desire to care for it). And to the degree that our virtual worlds are bespoke realities ostensibly constructed for us, whether they also deprive us of an experience of a common world, one we share with others, thus accentuating rather than alleviating an experience of alienation and isolation. Vision Pro, a set of goggles you literally place over your eyes, presents us with a viscerally dramatic symbol of such a deprivation. But, as I hope I’ve made clear, Vision Pro is not unique in this tendency. It is only one of many ways we might thus isolate ourselves from the world.

What then? Let’s put it this way. There are two ways to augment reality: virtually or by your attention—in the mode of the machine or in the mode of a creature.

For my part, I’ve fallen into a tradition of thought for which vision, attention, and contemplation are key categories of the good life. How a device called Vision Pro (and how, more broadly, all technologies that mediate vision and attention) can be understood from the perspective of such a tradition requires more reflection than I can justly give the subject in closing remarks. But I will note that Iris Murdoch is one of the key figures in this tradition, and I will give her the final word.

“It is in the capacity to love, that is to see, that the liberation of the soul from fantasy consists,” Murdoch insisted. “The freedom which is a proper human goal is the freedom from fantasy, that is the realism of compassion.” There are many uses to which our devices can be put, but it is, from this perspective, worth asking whether their pattern of use encourages a liberation of the soul—a liberation consisting in the capacity to direct a “just and loving gaze directed upon an individual reality”—or whether it encourages us to remain content in a realm of fantasy, which Murdoch defined as “the proliferation of blinding self-centered aims and images.”

You can read some reflections along these lines and taking their point of departure from Berry in a recent newsletter from David Mattin.

Putting it this way also acknowledges a measure of coercion that I’m sure Berry would also acknowledge but which the phrasing “wish to live” tends to veil.

In a helpful essay about Vision Pro in The New Atlantis, John Fechtel makes a similar observation: “Most of us do not have a strong enough sense of the indispensability of the body to resist having yet another layer of ourselves peeled away and a device put on us instead. Most of us already have devices too close to us, and our digital persona feels too real, and too far from our physical life, to resist the closing circle of each new epochal device. We need to get comfortable in our own skin again. To do this, we need courage and optimism.”

You left something vital out.

For an infant, attention and gaze are what water and sunlight are to a plant. If at the beginning of life a parent's eyes are hidden and attention is diverted into a machine, what does that teach a child? That only machines are valuable and worthy of attention. That I should form my attachments to and seek my fulfillment through machines, which I can control, not unreliable humans. The parent's behavior is both modeling these priorities and modeling the child's neurology to know no alternative. Starving the child of its birthright as a creature from the get-go.

Excellent essay, thank you so much. That old quote from Pascal comes to mind regarding why we are so prone to distractions, "The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me." Having lost our ability to hear (to be present to God and one another) we must find other ways to soothe our worried souls.