Welcome to The Convivial Society, a newsletter exploring the consequences of modern technology. Regular readers know that these installments are usually accompanied by an audio version, but being on the road means that I’m unable to provide the audio this time around. Sorry about that. As always, I trust this finds you well. And, if you enjoy the newsletter, consider sharing it with others and/or becoming a paid subscriber. Thanks for reading. I hope you find something worth thinking about.

“In 1957, an earth-born object made by man was launched into the universe, where for some weeks it circled the earth according to the same laws of gravitation that swing and keep in motion the celestial bodies—the sun, the moon, and the stars.”

This is how Hannah Arendt opened the Prologue to The Human Condition, which was published in 1958. Arendt went on to call the launch of Sputnik an event “second in importance to no other, not even to the splitting of the atom,” a sentiment that may seem rather quaint now that we have around 7,500 satellites in low earth orbit and several corporations, including SpaceX and Amazon, planning to put another 65,000 combined satellites in orbit in the coming years. But our familiarity and indifference is no argument against Arendt’s claim.

Arendt also noted that this momentous event was met with joy, although joy mixed with fear given the geopolitical circumstances. But this joy was of a curious sort. According to one American journalist cited by Arendt, it was a “step toward escape from men's imprisonment to the earth.” Arendt found in this claim an echo of an earlier statement by an eminent Russian scientist: “Mankind will not remain bound to the earth forever.”

Arendt went on to explain that such sentiments should not surprise us. We would have found the feeling altogether commonplace if only we’d looked for it in the right place. “Here, as in other respects,” Arendt observed,

science has realized and affirmed what men anticipated in dreams that were neither wild nor idle. What is new is only that one of this country's most respectable newspapers finally brought to its front page what up to then had been buried in the highly non-respectable literature of science fiction (to which, unfortunately, nobody yet has paid the attention it deserves as a vehicle of mass sentiments and mass desires).

Arendt believed, however, that the modern the desire to escape the earth, understood as a prison of humanity, was strikingly novel in human history. “Should the emancipation and secularization of the modern age,” Arendt wondered, “which began with a turning-away, not necessarily from God, but from a god who was the Father of men in heaven, end with an even more fateful repudiation of an Earth who was the Mother of all living creatures under the sky?”

I thought about Arendt as I listened to Jeff Bezos talk about space exploration at a recent event held at the National Cathedral, a setting that will strike those of you familiar with the late David Noble’s work in The Religion of Technology as altogether apropos. The thesis of Noble’s book was that “modern technology and religion have evolved together and that, as a result, the technological enterprise has been and remains suffused with religious belief.” In this light, a cathedral is an altogether appropriate setting for the annunciation of a not-so-novel message of technologically mediated salvation and transcendence.

Bezos was joined on stage by, among others, Avril Haines, Director of National Intelligence; former senator and current NASA Administrator, Bill Nelson; and Harvard professor, Dr. Avi Loeb.

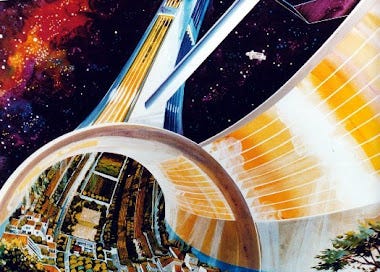

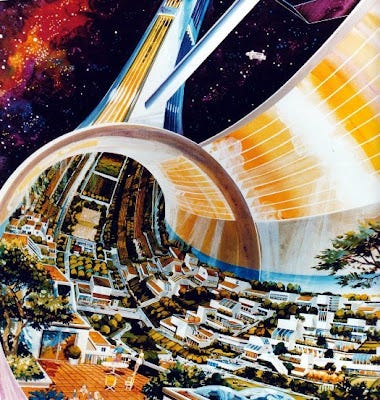

During his portion of the proceedings, which you can watch in the clip below, Bezos articulated a vision for the creation of space colonies that would eventually be home to millions of people, many of who would be born in space and would visit earth, Bezos explained, “the way you would visit Yellowstone National Park.”

That’s a striking line, of course. It crystalizes the earth-alienation Arendt was describing in Prologue of The Human Condition. It is, in fact, a double alienation. It is not only that these imagined future humans will no longer count the earth their home, it is also that they will perceive it, if at all, as a tourist trap, a place with which we have no natural relation and know only as the setting for yet another artificial consumer experience. And, put that way, I hope the seemingly outlandish nature of Bezos’s claims will not veil the more disturbing reality, which is that we don’t need to be born in space to experience the earth in precisely this mode.

To be sure, Bezos makes a number of statements about how special and unique the earth is and about how we must preserve it at all costs. Indeed, this is central to Bezos’s pitch. In his view, humanity must colonize space, in part, so that resource extraction, heavy industry, and a sizable percentage of future humans can be moved off the planet. It is sustainability turned on its head: a plan to sustain the present trajectories of production and consumption.

But, of course, as Bezos acknowledges, we are nowhere near the realization of this vision, should it even prove to be possible.1 In the meantime, one presumes, the degradation of the earth will continue apace. In fact, Bezos’s vision strikes me as a doubling down on the status quo: the ostensible solution is punted into the distant future, implying that nothing can or should change in meantime, certainly not the form of life centered on production and consumption.

But Bezos isn’t the only one selling earth-alienation, and there’s more than one way to give up on the earth. Earth alienation is also implicit in the drive to create ever more elaborate and immersive virtual realms, which include both our general information environment and our sophisticated entertainment apparatus. I’m reminded of another work that took Sputnik as a point of departure. Writing in 1974, Marshall McLuhan claimed, “Perhaps the largest conceivable revolution in information occurred on October 17th, 1957, when Sputnik created a new environment for the planet.” “At the moment of Sputnik,” he added, “the planet became a global theater in which there are no spectators but only actors.” And with a final flourish, McLuhan writes that with the launch of Sputnik “the planet moved up into the status of a work of art.”

In a rather well-known exchange with Norman Mailer from 1968, McLuhan pursued this line of thought:

In 1844, the first year of the commercial telegraph, Kierkegaard published a book called The Concept of Dread. He was quite aware that a new environment had formed around the old mechanical one. And whenever a new environment goes around an old one there is always new terror. And we live in a time when we have put a man-made satellite environment around the planet. The planet is no longer nature; it’s no longer the external world. It’s now the content of an artwork. Nature has ceased to exist.

Mailer presses McLuhan, conceding that what McLuhan is describing as a present fact is maybe 100 years out. We’re a little more than halfway there now, and a bit ahead of schedule, I’d say. McLuhan is, of course, speaking provocatively by claiming that the fact is more or less accomplished. And as I read McLuhan on this point, I think, too, of a recurring idea in Arendt’s The Human Condition, that of an Archimedean point.

Give me a place to stand, Archimedes was reputed to have claimed, and I can move the earth. In Arendt’s historical genealogy of our modern earth alienation, she found in the success of Galileo and his contemporaries the discovery of an Archimedean point of sorts:

Without actually standing where Archimedes wished to stand (dos rnoi pou sto), still bound to the earth through the human condition, we have found a way to act on the earth and within terrestrial nature as though we dispose of it from outside, from the Archimedean point. And even at the risk of endangering the natural life process we expose the earth to universal, cosmic forces alien to nature's household.

Arendt is thinking of the harnessing of nuclear power, a technology made possible by the assumption of a universal, Archimedean perspective by early modern physics. I read McLuhan’s claim that an environment of artificial satellites encasing the globe reframes our understanding of the earth. And, of course, McLuhan draws our attention to our information environment created by communication technologies. But these technologies are now increasingly marketed so as to render them avenues of escape and even as a solace for those who will be left out of emerging economic order.

Jon Scribner recently wondered whether “in a circular and sustainable economy (which likely would need to be low growth) could all conspicuous consumption move to the metaverse? Huge businesses are already being built on the virtual flex economy, which is... more environmentally friendly than buying a real lambo?” This is a striking parallel to Bezos framing of space colonies as a solution to the disorders of our present mode of relating to the earth, although Scribner is here merely thinking out loud. In neither case, though, is a third option contemplated—that we change our mode of relating to the world and correct the assumptions driving this way of life.

Of course, the two lines of thought are distinct, and I don’t want to suggest that McLuhan’s and Arendt’s arguments are perfectly compatible. But their invocation of Sputnik invited comparison, and both, in my view, help us reckon with the various dimension of the earth alienation now on offer as a service, which is partly a matter of seeking a literal departure from the earth and partly a matter of encasing ourselves in artificial environments, indeed of rendering the earth itself an artificial environment.

We are being sold a retreat from the human condition and its natural habitat, but McLuhan and especially Arendt help us to see that we are dealing with recent iterations of long-standing trajectories of thought and practice. In these more recent iterations, we are also tacitly offered an escape from responsibility and obligation, to each other and to the earth that is our common home. Although, perhaps more to the point, the two visions of retreat and escape constitute an evasion of responsibility by those whose interests would not be served by a reversal of our present course. But, lest those of us not funding private space travel let ourselves off the hook, I would quickly add that we are all to some degree complicit.

Tomorrow is Thanksgiving in the U.S., a holiday born out of fraught circumstances and which now dwindles in significance to the degree that it resists easy commercialization. Nonetheless, I’ll take the occasion to suggest again that there would be much to be gained by countering earth alienation with gratitude.

I am generally convinced by those who, in trying to characterize the modern, technological relation to the world, find that this relation is best described as a one of mastery and control, which is to say, a relation of power and, consequently, alienation. Positioned in this way, we are tempted to see the world, including ourselves, as a field of objects to be limitlessly manipulated and exploited.2

It would be hard to overestimate how productive this relation has been: it has yielded valuable fruit that we should not lightly discount. But it has not come without costs. The costs are material, social, psychic, and moral; and it seems safe to say that we still await a final accounting.

What alternative do we have to this stance toward the world that is characterized by a relation of mastery and whose inevitable consequence is a generalized degree of alienation, anxiety, and apprehension?

We have a hint of it in Arendt’s warning against a “future man,” who is “possessed by a rebellion against human existence as it has been given, a free gift from nowhere (secularly speaking), which he wishes to exchange, as it were, for something he has made himself.” We hear it, too, in Wendell Berry’s poetic reminder that “We live the given life, not the planned.” It is, I would say, a capacity to receive the world as gift, as something given with an integrity of its own that we do best to honor. It is, in other words, to refuse a relation of “regardless power, ” in Albert Borgmann’s apt phrase, and to entertain the possibility of inhabiting a relation of gratitude and wonder. In one way or another, all that I have to say about technology comes down to this. We must learn like Gloucester in King Lear to see the world and our life in it anew. We, like Gloucester bent in despair on taking his own life, must hear his son Edgar’s voice: “Thy life’s a miracle. Speak yet again.”

Bezos makes clear that he is not envisioning the proliferation of colonies on the model of the International Space Station, but rather grandiose artificial environments with gravity, streams, and vegetation—more or less as envisioned in the 1970s by Gerard O’Neil.

So many great insights here. I’m reminded of Wendell Berry’s essay, “The Use of Energy,” which, in the penultimate paragraph, he refers to none other than Ivan Illich. Forgive me for quoting parts of the concluding paragraphs at length here. They’re just so good and go so well with your essay.

“To argue for a balance between people and their tools, between life and machinery, between biological and machine-produced energy, is to argue for restraint upon the use of machines. The arguments that rise out of the machine metaphor—arguments for cheapness, efficiency, labor-saving, economic growth etc.—all point to infinite industrial growth and infinite energy consumption. The moral argument points to restraint; it is a conclusion that may be in some sense tragic, but there is no escaping it. Much as we long for infinities of power and duration, we have no evidence that these lie within our reach, much less within our responsibility. It is more likely that we will have either to live within our limits, within the human definition, or not live at all...

“The knowledge that purports to be leading us to transcendence of our limits has been with us a long time. It drives by offering material means of fulfilling a spiritual, and therefore materially unappeasable, craving: we would all very much like to be immortal, infallible, free of doubt, at rest. It is because this need is so large, and so in different in kind from all material means, that the knowledge of transcendence—our entire history of scientific “miracles”—is so tentative, fragmentary, and grotesque. Though there are undoubtedly mechanical limits, because there are human limits, there is no mechanical restraint. The only logic of the machine is to get bigger and more elaborate. In the absence of moral restraint — and we have never imposed adequate moral restraint upon our use of machines—the machine is out of control by definition. From the beginning of the history of machine-developed energy, we have been able to harness more power than we could use responsibly. From the beginning, these machines have created effects that society could absorb only at the cost of suffering and disorder.

“And so the issue is not of supply but of use. The energy crisis is not a crisis of technology but of morality. We already have available more power than we have so far dared to use. If, like the strip-miners and the “agribusinessmen,” we look on all the world as fuel or as extractable energy, we can do nothing but destroy it. The issue is restraint. The energy crisis reduces to a single question: Can we forbear to do anything that we are able to do? Or to put the question in the words of Ivan Illich: Can we, believing in “the effectiveness of power,” see “the disproportionately greater effectiveness of abstaining from its use”?

Great piece. As always - thank you.