“It appears to me that we cannot neglect the disciplined recovery, an asceticism, of a sensual praxis in a society of technogenic mirages. This reclaiming of the senses, this promptitude to obey experience, the chaste look that the Rule of St. Benedict opposes to the cupiditas oculorum (lust of the eyes), seems to me to be the fundamental condition for renouncing that technique which sets up a definitive obstacle to friendship.”

— Ivan Illich, “To Honor Jacques Ellul,” (1993)

I don’t usually write multi-part posts, but I did conclude an earlier installment with the promise of addressing one more development in the way I’ve come to think about attention. The essay here will (finally) pick up that thread. This post is a long one, so here’s the executive summary. Attending to the world is an embodied practice involving our senses, and how we experience our senses has a history. The upshot is that we might be able to meet the some of the challenges of the age by cultivating an askesis of perception.

As I explained last time around, I’ve been rethinking some aspects of how I talk about attention, a topic that has generated a great deal of interest in the age of digital media. I argued that we ought to reconsider the way the problem of attention tends to be framed by the logic of scarcity, which naturally lends itself to economic categories, and I suggested, too, that we proceed on the assumption that we have all the attention we need so long as that attention is properly ordered. What I have to say in this installment doesn’t exactly depend on those earlier reflections, but it’s probably worth mentioning that what follows picks up where I had left off in that essay.

The additional line of thought, which I want to pursue here, involves the relationship between attention and the body. The reflections that led me down this path began with the realization that attention discourse tends to abstract attention away from the body. When we talk about attention, in other words, we tend to talk as if this faculty had no particular relationship to the activities of the body.

This is not altogether surprising if we think about attention as the capacity to focus our thinking on a particular object. In this mode, attention is a strictly mental activity. We might even close our eyes in order to do it well. In this sense, attention becomes nearly synonymous with the activity of thinking itself. Or, alternatively, with prayer. It was Simone Weil, for example, who claimed that “absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.”

But this is not the only mode of attention, of course. More often than not, when we talk about attention in relation to digital media we are talking about our capacity to attend to something or someone out there in the world. What we are doing in such cases is somewhat different than what we do when we attempt to think deliberately about a problem, say, or when we are concentrating on a memory of the past. When we attend to the world beyond our head, to borrow the title of Matthew Crawford’s book from a few years back, we are doing so through the mediation of our perceptual apparatus: we are looking with our eyes, smelling with our noses, listening with our ears, feeling with our fingertips, or tasting with our mouths. In other words, attention discourse tends to make a mental abstraction out of an ordinarily embodied practice. (And, I’ll mention in passing that it’s probably worth reflecting on the fact that attention, if we link it to the senses at all, is almost always linked to either seeing or hearing.)

Consider, for example, this rather well-known paragraph from the American philosopher William James’s Principles of Psychology published in 1890:

“Everyone knows what attention is. It is taking possession of the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seems several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration of consciousness are of its essence. It implies a withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others.”

This is all fine and good, of course. It accords with how most of us think about attention. I’m not suggesting that attention is anything less than this, only that we might improve our understanding of what is happening when we attend to the world if we also attend to what our senses are up to when we do so. A determination to see may only get us so far if we do not also think about how we see or, and this will be a critical point, recognize that our seeing can be trained. Moreover, James’s definition of attention leaves little room for the role that beauty or desire or ethics might play in the dance between our consciousness and the world. Attention is reduced to the exercise of raw mental will-power.

As with my earlier discussion of the rhetoric of scarcity that treats attention as a resource, I don’t want to overstate my point here. I’m not suggesting that one should never speak about “attention” per se or that connecting attention more closely to our bodily senses will resolve our issues with attention. But, I do think there may be something to be gained in both cases. And here again I’m going to proceed with a little help from Ivan Illich, who, in the last phase of his intellectual journey, devoted a great deal of attention to the cultural history of the body and, specifically, sense experience.

I’ll start with a proposal Illich wrote for David Ramage, who was then president of McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago. What I’m calling a proposal, Illich titled “ASCESIS. Introduction, etymology and bibliography.” The short seven-page document details a plan for a five-year sequence of lectures that Illich wanted to give on the role ascetic disciplines might play in higher education. The proposed courses would each take up a focal point of bodily sense experience. To my knowledge, these lectures were never delivered. Nonetheless, the proposal and some of Illich’s other work around this time remains instructive.

To be clear at the outset, Illich was not calling for a return to the old ascetic disciplines we might associate with earlier monastic traditions, for example. “The asceticism which can be practiced at the end of the 20th century,” Illich explained, “is something profoundly different from any previously known.” Nor is it a specifically religious mode of asceticism that Illich has in mind. In his view the tradition he is reviving and re-working includes pagan philosophers as well as monastic scholars.

Illich thought that a rupture in this tradition had occurred sometime around the 12th century. This rupture had regrettably obscured the importance to learning of the body, including the affections.

“Learning presupposes both critical and ascetical habits; habits of the right and habits of the left,” Illich claimed. He added: “I consider the cultivation of learning as a dissymmetrical but complementary growth of both these sets of habits.” It wasn’t immediately obvious to me what Illich meant by habits of the right and the left, but in the same paragraph he goes on to mention “habits of the mind,” or the critical habits celebrated and cultivated in the humanist tradition of learning, and the consequent neglect of the “heart’s formation.” Interestingly, the latter task, in his estimation, had been lately relegated to “the media.”

“I want to explore the demise of intellectual asceticism as a characteristic of western learning since the time it became academic,” Illich went on to explain. “In this historical perspective,” he continued,

I want to argue for the possibility of a new complementarity between critical and ascetical learning. I want to reclaim for ascetical theory, method and discipline a status equal to that the University now assigns to critical and technical disciplines.

Reading Illich’s proposal from 1989, it strikes me as all the more relevant thirty years later. Confronted with the challenges of information superabundance, a plague of misinformation and digital sophistry, the collapse of public trust in traditional institutions, and algorithmically manipulated feeds, the “solutions” proffered, such as increased fact checking, warning labels, or media literacy training, seem altogether inadequate.

From Illich’s perspective, we might say that they remain exclusively committed to the habits of the mind or the critical habits. What difference might it make for us to take Illich’s suggestion and consider the ascetic habits or habits of the body, holistically conceived? Might we do better to think about attention not as a resource that we pay or squander at the behest of the attention economy and its weaponized digital tools but rather as a bodily skill that we can cultivate, train, and hone?

To explore these questions, let’s walk through parts of two other pieces by Illich, “Guarding the Eye in the Age of Show” and “To Honor Jacques Ellul.” The former is one of the last things Illich wrote just two years before his death in 2002. It is a 50-page distillation of his research in the cultural history of visual perception or the ethics of the gaze. The latter was, as the title suggests, a brief 1993 talk given in honor of the great critic of modern technology whose work had deeply informed Illich’s perspective.

“Guarding the Eye in the Age of Show,” were it written today, might be classified as a contribution to attention discourse, except that the word attention is used in this sense only once, and the same is true of its nemesis distraction. Instead, Illich speaks of the ethical gaze or of what we do with our eyes and also how we conceive of vision itself, which as it turns out has a very interesting history (for more about that history, see another paper by Illich, “The Scopic Past and the Ethics of the Gaze”).

So, here is Illich’s mention of attention in a way that echoes contemporary attention discourse: “Even today, I feel guilty if I find my attention distracted from a medieval Latin text by the afterglow of the MTV to which I exposed my eyes.” (Who amongst us has not …) Setting aside the question of why Illich was watching MTV, let’s consider a bit more carefully what Illich has to say here.

He goes on to explain how “until quite recently, the guard of the eyes was not looked upon as a fad, nor written off as internalized repression. Our taste was trained to judge all forms of gazing on the other. Today, things have changed. The shameless gaze is in.” Illich was quick to add that he was not speaking of gazing at pornographic images. He was interested in recovering the idea that seeing was an action and not merely a passive activity on the model of a lens receiving visual data. And, as an action, it had an ethical dimension (Illich was very much indebted to the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas on these matters).

He was concerned, too, with the way the gaze was captured or trapped by what he termed “the show.” Illich used show to distinguish the object of perception from the image, which had played such a critical if evolving role in traditional western philosophy and religion. At one point, he puts the question he wants to address this way: “What can I do to survive in the midst of the show?” A question that, I suspect, still resonates today.

Surviving the Show

So what exactly was the show? I’m tempted to say that we can think of it simply as what we take in when we glance at any of our screens. I don’t think Illich would disagree with that assessment, but that’s obviously not a very helpful definition and it’s clear that Illich thought the show was a broader phenomenon. The truth is that I find it difficult to precisely pin down what Illich had in mind, but let me at least try to fill out the concept a bit more.

Illich says at one point that “the distinction between image and show in the act of vision, though subtle, is fundamental for any critical examination of the sensual "I-thou" relationship. To ask how I, in this age and time, still can see you face-to-face without a medium, the image, is something different from asking how I can deal with the disembodying experience of ‘your’ photographs and telephone calls, once I have accepted reality sandwiched between shows.”

Here, two things are clear. Illich is striving to preserve the possibility of “seeing” the person before our eyes, and the show, as he understands it, the pervasive field of technological mediations that shape our perception of the other threatens to obscure our ethical vision. I think of the way this very language has emerged to describe the act of beholding the person in a morally substantive way. We hear, for example, of the desire to “be seen,” by which, of course, something much deeper is in view than merely appearing within someone’s visual field. Or, somewhat less seriously, we joke about “feeling seen,” which is to say that some meme has come uncomfortably close to capturing some aspect of our personality.

Further on in the paper Illich writes, “I argue that ‘show’ stands for the transducer or program that enables the interface between systems, while ‘image’ has been used for an entity brought forth by the imagination. Show stands for the momentary state of a cybernetic program, while image always implies poiesis. Used in this way, image and show are the labels for two heterogeneous categories of mediation.”

My sense, deriving from the passing reference to cybernetics, is that the distinction between the image and the show tracks with the distinction, critical to Illich’s later work, which he drew between the age of instruments and the age of systems. While I don’t think that Illich rigorously developed this distinction anywhere in writing, one key element involved the manner in which the system, as opposed to the mere instrument, enveloped the user. It was possible to stand apart from the instrument and thus to attain a level of mastery over it. It was not possible to likewise stand apart from the system. Which may explain why Illich, as we’ll see shortly, concluded, “There can be rules for exposure to visually appropriating pictures; exposure to show may demand a reasoned stance of resistance.”

Elsewhere he says that in our present media ecosystem our gaze is sometimes “solicited by images, but at other times it is mesmerized by show.” The difference between solicitation and mesmerization seems critical. It is in this context that he also writes, “An ethics of vision would suggest that the user of TV, VCR, McIntosh and graphs protect his imagination from overwhelming distraction, possibly leading to addiction.”

Extrapolating a bit, then, and even taking the word show at face value, we might say that there was something dynamic and absorbing about the show that distinguished it from the image. (Let me say at this point that I’m not getting into Illich’s discussion of the image, which takes up classical philosophy and medieval theology. Click through to read the whole paper for that discussion.)

Things then get a bit more interesting toward the tail end of the article as Illich brings his historical survey of the gaze into the modern era. If we thought that Illich was connecting the show exclusively to the age of electronic media or even the proliferation of images in the late nineteenth century, we might be taken aback when he claims that “the replacement of the picture by the show can be traced back into the anatomical atlases of the late eighteenth century.” It’s a good reminder that, as eclectic as Illich’s talents and interests were, he always remained, in some fundamental sense, a historian.

“With the transition from the age of pictures to the age of show,” Illich had just written, “step by step, the viewer was taken off his feet. We were trained to do without a common ground between the registering device, the registered object and the viewer.” I hear echoes in these lines of Baudrillard, but not quite. It is not an image that has no referent in the world but rather a way of relating to the world that has no referent in our experience, a mediation of the world that displaces the ordinary or even carefully trained mediation of the human sensorium.

Citing the work of his frequent collaborator, Barbara Duden, Illich writes, “the anatomists looked for new drawing methods to eliminate from their tables the perspectival ‘distortion’ that the natural gaze inevitably introduces into the view of reality.” “They want a blueprint of the object” he adds, and “They want measures, not views. They look at the world, more architectonico, according to the layout of architectural drawings.” The new scopic regime, as he calls it, spills out from anatomy to geology and zoology. “Thanks to the new printing techniques,” Illich concludes, “the study of nature increasingly becomes the study of scientific illustrations.”

This incipient form of the show appears to involve a means of representation that abstracts perception from the bodily frame of reference. It presents us with a view of the world that, while highly generative in many respects, may nonetheless leave us ill prepared to see the world as it is available to us through sense experience.

One of the more compelling bits of evidence Illich marshals in his historical investigations involves the shrinking diversity of words to designate varieties of sense experience. Summarizing the work of a variety of scholars, Illich noted,

Dozens of words for shades of perception have disappeared from usage. For what the nose does, someone has counted the victims: Of 158 German words that indicate variations of smell, which Dürer's contemporaries used, only thirty-two are still in use. Equally, the linguistic register for touch has shriveled. The see-words fare no better.

Sadly, this accords with my own experience, and I wonder whether it rings true for you. Upon reflection, I have a paucity of words at my disposal with which to name the remarkable variety of experiences and sensations that the world offers.

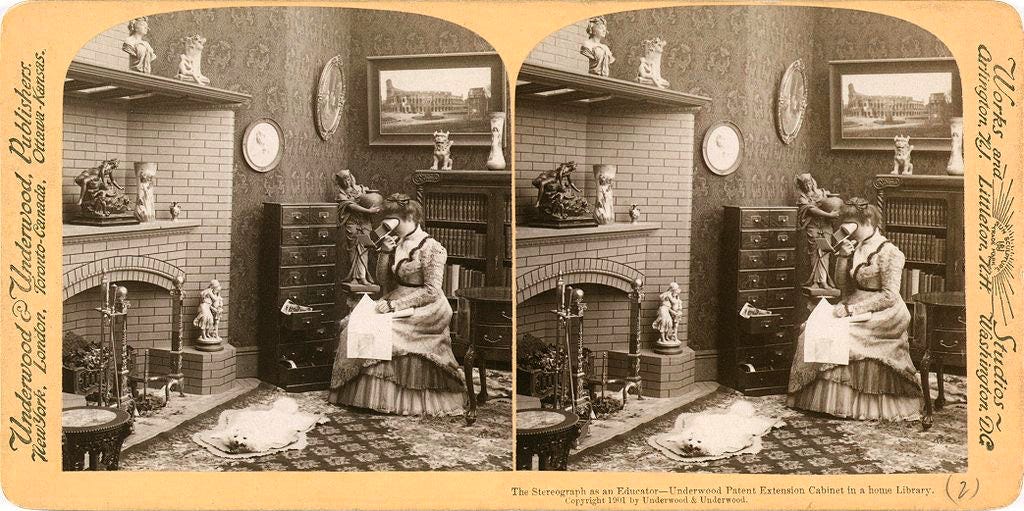

Picking up the storyline again, the incipient form of the show was then reinforced or perhaps Illich would say popularized by the advent of the stereoscope (pictured below). The stereoscope is one of several widely used nineteenth century devices for manipulating visual experience. The Claude glass is another example that comes to mind. Illich described the stereoscope as follows:

“Two simultaneous exposures are made next to each other on the same photographic plate through two lenses distanced from each other by a few inches. The developed picture postcard is placed into a box and viewed through a pair of special spectacles. The result is a ‘surrealist’ dimensionality. The foreground and background that lie outside the focus are fuzzy, while the focused object floats in unreal plasticity.”

He noted that his grandmother, in the early twentieth century was still bringing back these stereo cards from her travels.

Speaking of the emergence of the scopic regime of the show in the early nineteenth century, Illich concluded, “New optical techniques were used to remove the picture of reality from the space within which the fingers can handle, the nose can smell and the tongue can taste it, and show it in a new ‘objective’ isometric space into which no sentient being can enter.”

It may be helpful to draw in Illich’s evolving critique of medicine for an example of the show that is not directly related to what we typically think of media technology. During the 1980s, as the consequences of the shift from instruments to systems was dawning on Illich, he came to see that one of the harms of modern institutionalized medicine was the implicit displacement of the lived body by the body that is a system apprehended by diagnostic tools. It is the body reduced to one’s chart, health as conformity to statistical averages and patterns. The individual and the particularities of their body are lost. I don’t know that Illich ever puts it this way, but it seems clear to me that this can be understood as medicine in thrall of the show. It is not, of course, that such information is useless, rather it is that something is lost when our vision of the human is thus reduced to data flows, and that loss, difficult or perhaps impossible to quantify, can result in profound consequences. It can, for example, in the case of medicine, generate, paradoxically, greater forms of suffering.

Ocular Askesis

As he made clear at the outset of this paper, Illich undertook this examination of the history of visual perception in order to explore the ethics of the gaze and how “seeing and looking is shaped by personal training (the Greek word would be askesis), and not just by contemporary culture.” Or, as he also put it, “My motive for studying the gaze of the past is a wish to rediscover the skills of an ocular askesis.”

In other words, Illich invites us to consider what it might mean to discipline our vision, and I’m inviting us to consider whether this is not a better way of framing our relationship to the digital media ecosystem. The upshot is recognizing the additional dimensions of what is often framed as a merely intellectual problem and thus met with laughably inadequate techniques. Perceptual askesis would involve our body, our affections, our desires, and our moral character as well as our intellect.

The first step would be to recognize that vision is, in fact, subject to training, that it is more than the passive reception of sensory data. In fact, of course, our vision is always being disciplined. Either it happens unwittingly as a function of our involvement with the existing cultural structures and patterns, or we assume a measure of agency over the process. Illich’s historical work, then, denaturalizes vision in order to awaken us to the possibility of training our eyes. Our task, then, would be to cultivate an ethos of seeing or new habits of vision ordered toward the good. And, while the focus here has fallen on sight, Illich knew and we should remember that all the senses can be likewise trained.

“Guarding the Eyes in the Age of Show” is a long and scholarly article. Illich’s comments in honor of Jacques Ellul, delivered a few years earlier, cover much of the same ground in a more direct, urgent, and prophetic style. It will be worth our time, I think, to close by considering some of these comments because they might give us a better idea of the nature of the good, in Illich’s view, toward which a perceptual askesis should be ordered.

In one of the clearest statements of the concerns that were animating his work during this time, Illich declared that “existence in a society that has become a system finds the senses useless precisely because of the very instruments designed for their extension. One is prevented from touching and embracing reality.” And, what’s more, “it is this radical subversion of sensation that humiliates and then replaces perception.”

In a similar dire vein, Illich continued: “We submit ourselves to fantastic degradations of image and sound consumption in order to anesthetize the pain resulting from having lost reality.” He then added: “To grasp this humiliation of sight, smell, touch, and not just hearing, it was necessary for me to study the history of bodily acts of perception.”

What is evident here is that Illich wanted to defend a way of being in the world that took the body as its focal point. He spoke of this as a matter of “touching and embracing reality.” While I’m deeply sympathetic to Illich’s point of view here, I think I might put things a bit differently. Reality is a bit too elastic and protean a term to be helpful in this case. Better, in my view, to make the case that we risk missing out on a fuller experience of the depth and diversity of things, along with the pleasures and satisfactions such an experience might yield.

It seems to me relatively uncontroversial to observe that, for example, looking can be distinguished from seeing. I might look at a painting, for instance, and fail to see it for what it is. The same is true of a landscape, a single tree, a bird, an elegant building, or, most significantly, a person. If my vision is trained by the show, will I be able to see the person before me who cannot match the show’s dynamic, mesmerizing quality? And, from Illich’s perspective, it is not only that I would fail to accord my neighbor the honor they are owed but that I would lose myself in the process, too. Eyes trained by the show would be unable “to find joy in the only mirror in which I can discover myself, the pupil of the other.”

News and Resources

A review of Frank Pasquale’s New Laws of Robotics, “A World Ruled by Persons, Not Machines”:

“Frank Pasquale’s thought-provoking and deeply humanist New Laws of Robotics: Defending Human Expertise in the Age of AI pledges that another story is possible. We can achieve inclusive economic prosperity and avoid both traps of mass technological unemployment and low labor productivity. His central premise is that technology need not dictate our values, but instead can help bring to life the kind of future we want. But to get there we must carefully plan ahead while we still have time; we cannot afford a ‘wait-and-see’ approach.”Douglas Rushkoff on “why people distrust ‘the Science’”:

“By disconnecting science from the broader, systemwide realities of nature, human experience, and emotion, we rob it of its moral power. The problem is not that we aren’t investing enough in scientific research or technological answers to our problems, but that we’re looking to science for answers that ultimately require human moral intervention.”Chad Wellmon is always insightful on the history of higher education. Here he is answering the question, “What must one believe in to be willing to borrow tens of thousands of dollars in order to pursue a certification of completion — a B.A.?”:

“Atop this pyramid scheme sit institutions like my own, the University of Virginia, which masks its constant competition for more — more money, more status, more prestige — as a belief in higher learning. Given the goals they set for themselves, UVA and other wealthy institutions need the system of higher education to continue just as it is. They profess to do so out of a faith that meritocracy’s hidden hand will watch over their graduates, ensuring the liberal, progressive order. And they hire professionals to manage that faith, such as UVA’s recently appointed vice provost for enrollment, who will ensure the most efficient use of students’ hopes in higher education to maximize revenues.”An essay adapted from The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information by Craig Robertson:

“The filing cabinet does not just store paper; it stores information; and because the modern world depends upon and is indeed defined by information, the filing cabinet must be recognized as critical to the expansion of modernity. In recent years scholars and critics have paid increasing attention to the filing systems used to store and retrieve information critical to government and capitalism, particularly information about people — case dossiers, identification photographs, credit reports, et al. 4 But the focus on filing systems ignores the places where files are stored. 5 Could capitalism, surveillance, and governance have developed in the 20th century without filing cabinets? Of course, but only if there had been another way to store and circulate paper efficiently. The filing cabinet was critical to the infrastructure of 20th-century nation states and financial systems; and, like most infrastructure, it is often overlooked or forgotten, and the labor associated with it minimized or ignored.”Opening of a review of Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures by Merlin Sheldrake:

“Try to imagine what it is like to be a fungus. Not a mushroom, pushing up through damp soil overnight or delicately forcing itself out through the bark of a rotting log: that would be like imagining the grape rather than the vine. Instead try to think your way into the main part of a fungus, the mycelium, a proliferating network of tiny white threads known as hyphae. Decentralised, inquisitive, exploratory and voracious, a mycelial network ranges through soil in search of food.”On the story of Robert McDaniel, who in 2013 was identified as a potential victim or perpetrator of a violent crime by a predictive policing algorithm:

“He invited them into this home. And when he did, they told McDaniel something he could hardly believe: an algorithm built by the Chicago Police Department predicted — based on his proximity to and relationships with known shooters and shooting casualties — that McDaniel would be involved in a shooting. That he would be a “party to violence,” but it wasn’t clear what side of the barrel he might be on. He could be the shooter, he might get shot. They didn’t know. But the data said he was at risk either way.”

Increasingly, it seems to me that we are presented with two paths along which we might make our way in the world. These two paths can be characterized in any number of ways. One path is marked by the desire to control experience, even the experience of others, and predictive technologies serve this purpose. The other path is marked by a greater degree of openness to experience in the interest of freedom, with the risks this entails, and, as I’ve suggested elsewhere, relies on promise rather than prediction.In light of the turn toward privacy in the tech industry, Evgeny Morozov wonders whether it was a mistake to put so much emphasis on matters of privacy in an effort to meet the challenges posed by big tech corporations:

“Yet I wonder if these surprising victories for the privacy movement may, in the end, turn out to be pyrrhic ones – at least for the broader democratic agenda. Instead of reckoning with the broader political power of the tech industry, the most outspoken tech critics have traditionally focused on holding the tech industry to account for numerous violations of existing privacy and data protection laws.”

While not specifically focusing on the privacy critique, three years ago I wrote in my first piece for The New Atlantis that whatever we make of the so-called tech backlash, it was not a serious critique of contemporary technology. I tend to think that piece holds up pretty well.Interesting essay in Real Life by Lauren Colleen:

“The technologies that evoke synaesthetic fallacy expedite the easy translation of all experience into data, and all data into capital. At the same time they mystify this process, cloaking it in the language of scientized magic. Synaesthetic fallacy is wielded as a tool for re-branding the interfaces that serve the data economy as essential mediators of a broken relationship between screen-obsessed humans and the external world. It seduces us into the illusion that tech can ever function as simply a neutral translator.”

Re-framings

— From an interview with Suzanne Simard in Emergence Magazine. By the way, Emergence is a really interesting and beautifully put together publication. You should check it out.

EM Throughout your work, you’ve kind of departed from conventional naming in many ways—“mother,” “children,” “her.” You use very unscientific terms—and, it seems, quite deliberately, as you just described—to create connection, relationship. But it’s not the normal scientific practice.

SS No, it’s not, and I can hear all the criticisms going on, because in the scientific world there are certain things that could kill your career, and anthropomorphizing is one of those things. But I’m at the point where it’s okay; that’s okay. There’s a bigger purpose here. One is to communicate with people, but also—you know, we’ve separated ourselves from nature so much that it’s to our own demise, right? We feel that we’re separate and superior to nature and we can use it, that we have dominion over nature. It’s throughout our religion, our education systems, our economic systems. It is pervasive. And the result is that we have loss of old-growth forests. Our fisheries are collapsing. We have global change. We’re in a mass extinction.

I think a lot of this comes from feeling like we’re not part of nature, that we can command and control it. But we can’t. If you look at aboriginal cultures—and I’ve started to study our own Native cultures in North America more and more, because they understood this, and they lived this. Where I’m from, we call our aboriginal people First Nations. They have lived in this area for thousands and thousands of years; on the west coast, seventeen thousand years—for much, much longer than colonists have been here: only about 150 years. And look at the changes we’ve made—not positive in all ways.

Our aboriginal people view themselves as one with nature. They don’t even have a word for “the environment,” because they are one. And they view trees and plants and animals, the natural world, as people equal to themselves. So there are the Tree People, the Plant People; and they had Mother Trees and Grandfather Trees, and the Strawberry Sister and the Cedar Sister. And they treated them—their environment—with respect, with reverence. They worked with the environment to increase their own livability and wealth, cultivating the salmon so that the populations were strong, the clam beds so that clams were abundant; using fire to make sure that there were lots of berries and game, and so on. That’s how they thrived, and they did thrive. They were wealthy, wealthy societies.

I feel like we’re at a crisis. We’re at a tipping point now because we have removed ourselves from nature, and we’re seeing the decline of so much, and we have to do something. I think the crux of it is that we have to re-envelop ourselves in our natural world; that we are just part of this world. We’re all one, together, in this biosphere, and we need to work with our sisters and our brothers, the trees and the plants and the wolves and the bears and the fish. One way to do it is just start viewing it in a different way: that, yes, Sister Birch is important, and Brother Fir is just as important as your family.

Anthropomorphism—it’s a taboo word and it’s like the death knell of your career; but it’s also absolutely essential that we get past this, because it’s an invented word. It was invented by Western science. It’s a way of saying, “Yeah, we’re superior, we’re objective, we’re different. We can overlook—we can oversee this stuff in an objective way. We can’t put ourselves in this, because we’re separate; we’re different.” Well, you know what? That is the absolute crux of our problem. And so I unashamedly use these terms. People can criticize it, but to me, it is the answer to getting back to nature, getting back to our roots, working with nature to create a wealthier, healthier world.

The Conversation

Reminder: the previous post announced the results of my experiment with much shorter, “is this anything?” posts. The feedback was overwhelmingly positive, so you can expect one or two of those in the coming days.

Also in the last post, I suggested that if you were not keen on supporting the Convivial Society directly through this platform, you could name a price on my ebook. The response indicated that it might be worthwhile to offer a standing alternative, so I created some subscription options through Gumroad. And, finally, if you value the newsletter, please consider yourself duly encouraged to share it with others.

Cheers,

Michael

Surviving the Show: Illich And The Case For An Askesis of Perception